Guiding principles for strategic communications work

This Strategic Communications Incubator resource outlines three core guiding principles that underlie and inform planning and practice towards hitting the theory of change targets in a strategic communications intervention. The three principles are listed in the following diagram:

Core idea

Progressives must lead the debate and be proactive in driving the agenda to broaden the narrative space in the public debate, rather than focus all their efforts on reacting to opposition narratives and arguments. The task for advocates is to reframe the debate in order to ‘change the weather’, and have the conversation they want to have1 .

Background

Many progressives recognise that in the last decade they are losing the middle ground in the broader public debates on rights issues such as migration and civic space. In response, there has been a tendency to focus on countering the opposition, based on an understandable outrage at continual populist attacks and the mainstreaming of right-wing narratives. While response is necessary, theory and practice show that it is far from sufficient to win back the middle ground. In fact, from a framing perspective, focusing mainly on responses means progressives are trapped in the opposition narrative while others are setting the agenda2 .

To change this dynamic, or “change the weather”, progressives need to lead the debate with their values3 . In practical terms, this means getting out in front with more of their own messages that will engage target audiences based on shared experiences and values. In this way, progressives can open up a new conversation, and have the conversation they want to have.

While problem/issue-, facts- and rights-driven approaches will still work to engage and mobilise supporter/base groups, value-based messages resonate more with broader public audiences because they touch emotions and connect with people’s core beliefs. As a result, they are more likely to move people to action4 . This is because people change their mind through emotional stimuli (relating to personal, lived experience), rather than rational stimuli (facts and rights), according to research from cognitive science, linguistics and social psychology5 and practice from international narrative change campaigning6 . We are not advising progressives to avoid talking about problems/issues, facts and rights, but to carefully sequence their approach: start with values and stories to engage people and bring them to the table, and then talk about issues, rights, and facts.

Core idea

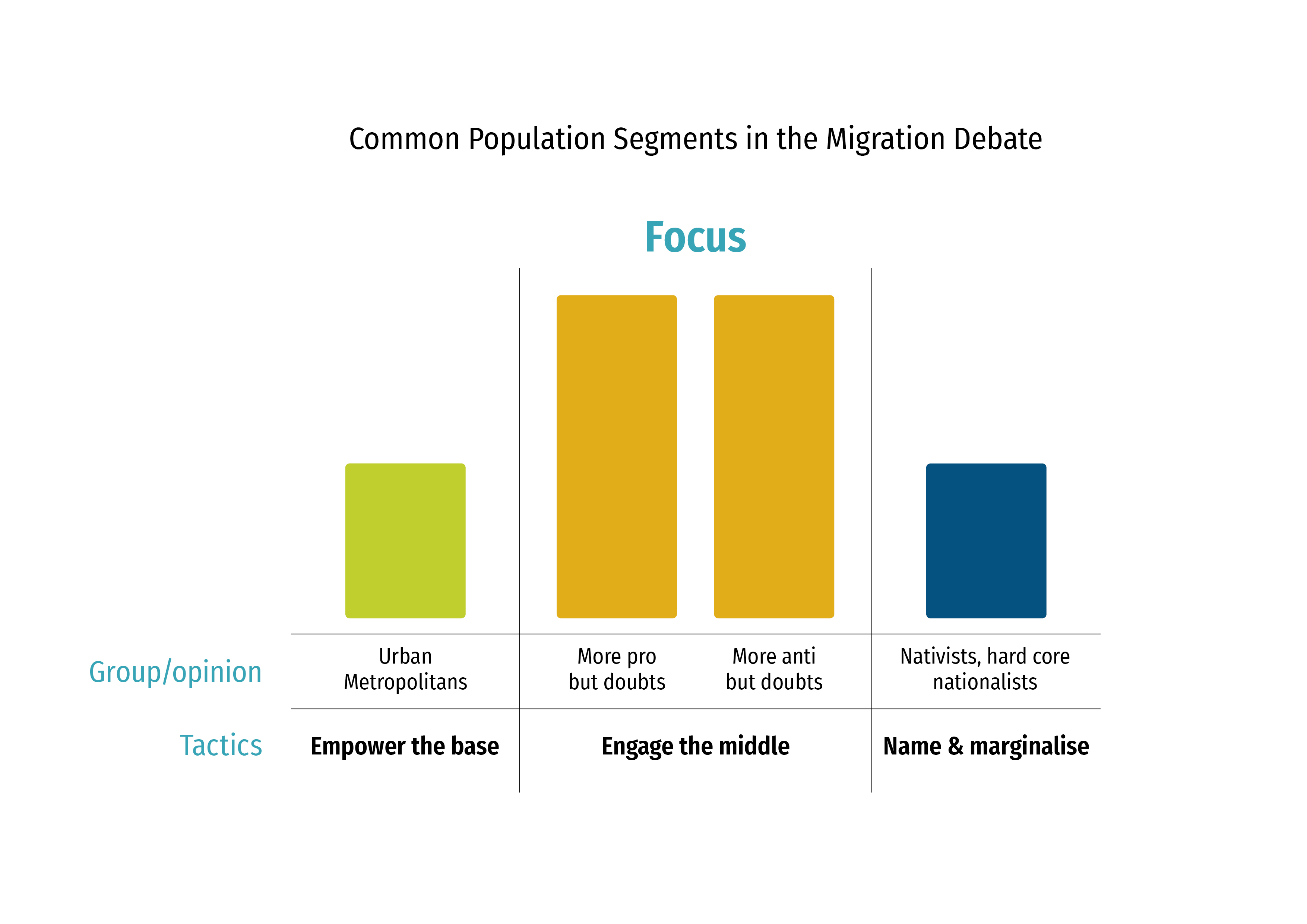

Progressives need to engage different segments of the public with separate tactics to serve their overall narrative strategy:

- Empower the base/supporters;

- Engage the middle;

- Name and marginalise extreme opponents

Background

Advocates tend to see the public falling into two camps: supporters and opponents. In fact, based on extensive polling, in most countries there is a breakdown of approximately 15% supporters, 15% opponents and 70 % in the middle (people who are unsure and undecided on many issues)7 . The good news from this research is that the majority and untapped potential are in the middle and it’s possible to change their minds. So, if progressives want to win the debate, they first need a more complicated view of the public and then broaden their target audiences to also include the majority8 .

Research9 shows that advocates need to determine which message to use to effectively reach and engage different groups, because each groups will react differently. In thinking about who to target, it could be the support base (who already agree with the advocate's position, but still may need to be empowered and mobilised) or the middle (who are neither for nor against, and are movable). Facts and rights arguments appeal to supporters, but advocates need to reframe to engage middle groups. Naming and marginalising opponents is based on the assumption that more extreme views are very difficult to change and hence, this tactic strengthens support in the base and middle by isolating more extreme views from the mainstream (for example, Hope not Hate, takes this approach). It is only broader coalitions or big, well-resourced organisations who can focus on all three segments (such as Welcoming America). Most organisations concentrate on building their capacities and infrastructure to pursue one or maybe two tactics.

Core idea

Progressives should embrace a smart network/movement perspective with partners, seeing their work stitched into the broader shared impact goal of the movement, rising above short-term individual interests. This entails building partnerships based on complementary roles, skills and access, co-ordinate their work, and share resources and lessons learned.

Background

In our work supporting advocates to date, a question that always comes up is: what can be achieved by one campaign? And of course, the answer is relatively small-scale change, in comparison to the greater challenge of shifting norms to change rules. In embracing a smart networking approach10 , the core of this guiding principle is to keep the shared impact goal of the progressive social movement in mind during planning (rather than only the goals of the individual's organisation). Recognising where they are adding value, guides in building partnerships based on complementary roles, skills and access, and coordinating with those who can sustainably drive new narratives at scale11 .

To quote one of our key partners, Frank Sharry from America’s Voice:

|

“To practice strategic comms in a way that shifts norms, we must ask: how we can build the strongest possible base of unity so we can go forward together? We must build a movement. We need different players on the field – some playing defence, some playing offence, some playing the centre, some playing the different wings. When the team is playing together is when you score goals. We talk about “movement" as a way of valuing all the different contributions. We all come from different places, but we are united by shared ideas and ideals. We strive for unity but not uniformity. We understand and accept there’s going to be different campaigns, different messages and different messengers for different audiences.” |

- 1Read more from International Centre for Policy Advocacy’s Reframing Migration Narratives toolkit: Introduction to the toolkit: “Why a reframing approach” and Step 0.1 of the toolkit “understanding the power of frames”

- 2Lakoff, G (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate : the essential guide for progressives. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co.

- 3For more information on the reason for a values-based approach, see our page: “Why a reframing approach”.

- 4Ganz, M (2011). “Public Narrative, Collective Action, and Power.”; Odugbemi, A and Lee, T (2011). Accountability through Public Opinion: From Inertia to Public Action. World Bank Group. pp. 269-286.

- 5Lakoff, G (2002) Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; Lakoff, G (2014). Don't think of an elephant!: know your values and frame the debate : the essential guide for progressives. 2nd Edition. White River Junction, Vt, Chelsea Green Pub. Co. Kahneman, D (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York.

- 6US – America’s Voice; Frameworks Institute; The Narrative Initiative; Welcoming America; & UK – British Future; HOPE not hate; Migration Exchange; Social Change Initiative.

- 7See this kind of public attitudes segmentation research from multiple countries in More in Common’s publications.

- 8Working Narratives (2013). "How do we reach new audiences" in Storytelling and social change: a strategy guide; Active Voice Lab’s “Beyond the Choir” tool; Beautiful Trouble’s “Consider your audience”.

- 9Specifically, audience segmentation and frames maps. Read more from International Centre for Policy Advocacy’s Reframing Migration Narratives toolkit: Step 1.1: “Target middle segments & their current frames”.

- 10Jon M. Waitzer and Roshan Paul, Scaling Social Impact: when everybody contributes, everybody wins; John Kania and Mark Kramer, 2011, Collective Impact, Stanford Social Innovation Review

- 11For those interested in the practice of working at scale in coalitions, see our “10 Keys to mobilise strategic communications coalitions”