Lesson 3 - The ‘movable middle’ are key to building support for CSOs at scale

Essence

It’s motivating to know that it IS possible to get a majority of the public on board to support civil society! And getting support from the persuadable majority in the middle can be the key to achieving attitude change at scale.

Insight

Many CSOs operating in more authoritarian contexts understandably doubt the chances of (re)building support and trust in the civil society sector and civic action beyond the sector and its supporters. This doubt comes from the harshness of the widely shared vilification narratives and smear campaigns on CSOs, and the increasing uptake of such narratives online among the wider public. This despair is understandable in some contexts as the narrative attacks and clampdowns on the sector are intense and continue with impunity.

However, this is far from being a lost cause! The good news is that extensive polling and segmentation of public attitudes shows that the majority of the public (often 60% to 70%) lie between strong supporters and opponents at either end of the spectrum1

. We are among many other narrative change practitioners and experts who call this majority the ‘persuadable’ or ‘movable’ middle’ or ‘balancers’. Such movable middle segments tend to be:

- those who are not that involved or engaged in the target issue;

- quite easily influenced and convinced by the dominant public narratives;

- quite conflicted, anxious and frustrated about ongoing debates.

In our experience, these middle segments in civic space debates care about democracy and civic rights, but are also influenced by attack narratives that undermine trust in CSOs. The good news is that our empirically-tested experience in Kazakhstan and Germany has shown that effective messaging to these groups on shared values, aspirations and concerns (also around wedge issues) can lead to a significant positive shift in their attitudes on CSOs. Hence, convincing these audiences is key to creating the public support needed to prevent further attacks and restrictions on civic space.

A caveat that we repeat as often as possible: Such a middle-oriented strategy is NOT intended to replace work to mobilise supporters and/or marginalise opponents. We advocate for adding this middle-oriented approach to your broader advocacy toolbox, if this is a suitable strategy for you and your organisation. Hence, the strategy we (and others) propose is a “both/and, not either/or”2

approach (See narrative change key, number 1 for more on this).

Cases

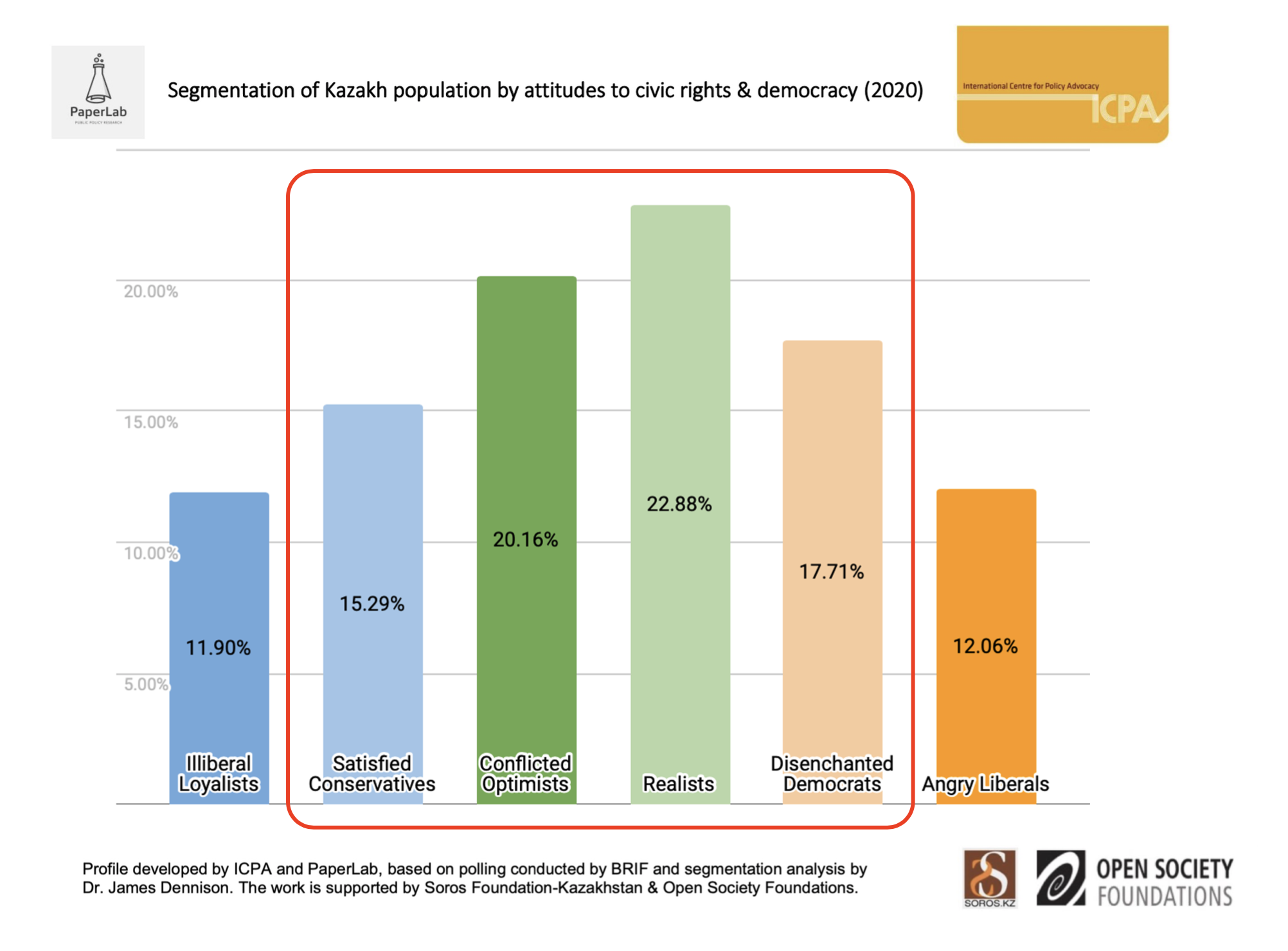

Figure 4 – Movable middle segments in civic space debate in Kazakhstan

The campaign videos and social media content from the #Azamatbol campaign3

targeting three of these middle segments achieved a significant shift in public attitudes on key attitudes to CSOs and civic engagement in the positive. (See the cases section on for more details on the evaluation results of the Kazakh campaign).

- Hungary - Instead of getting caught up in the polarising and demoralising back and forth of government attacks on their organisation and the civil society sector, Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) decided to try to expand its support with the persuadable middle by sharing the positive, hopeful and human stories of those they support and of the staff of the organisation in a campaign called ‘HCLU is needed!’4

. As reported, this succeeded in significantly expanding their social media following and donations in a period of ongoing public attacks5

.

- Egypt – Human rights defenders who support victims of domestic violence came under attack from the authorities as alleged promoters of ‘Western values’, making it increasingly difficult for them to do their community work, as the attacks led to a hostile and dangerous environment. Working to reduce anxiety among movable middle families, they were able to engage religious leaders as their messengers who successfully argued the key role of CSOs, especially that those protecting women’s rights make to families and the stability of the country. This intervention served to rebuild trust at the local levels and allowed them to return to their clients in safety6

.

See the Advocacy Cases Section 6 for more detail and background on the Kazakh case and footnotes for the others.

Action

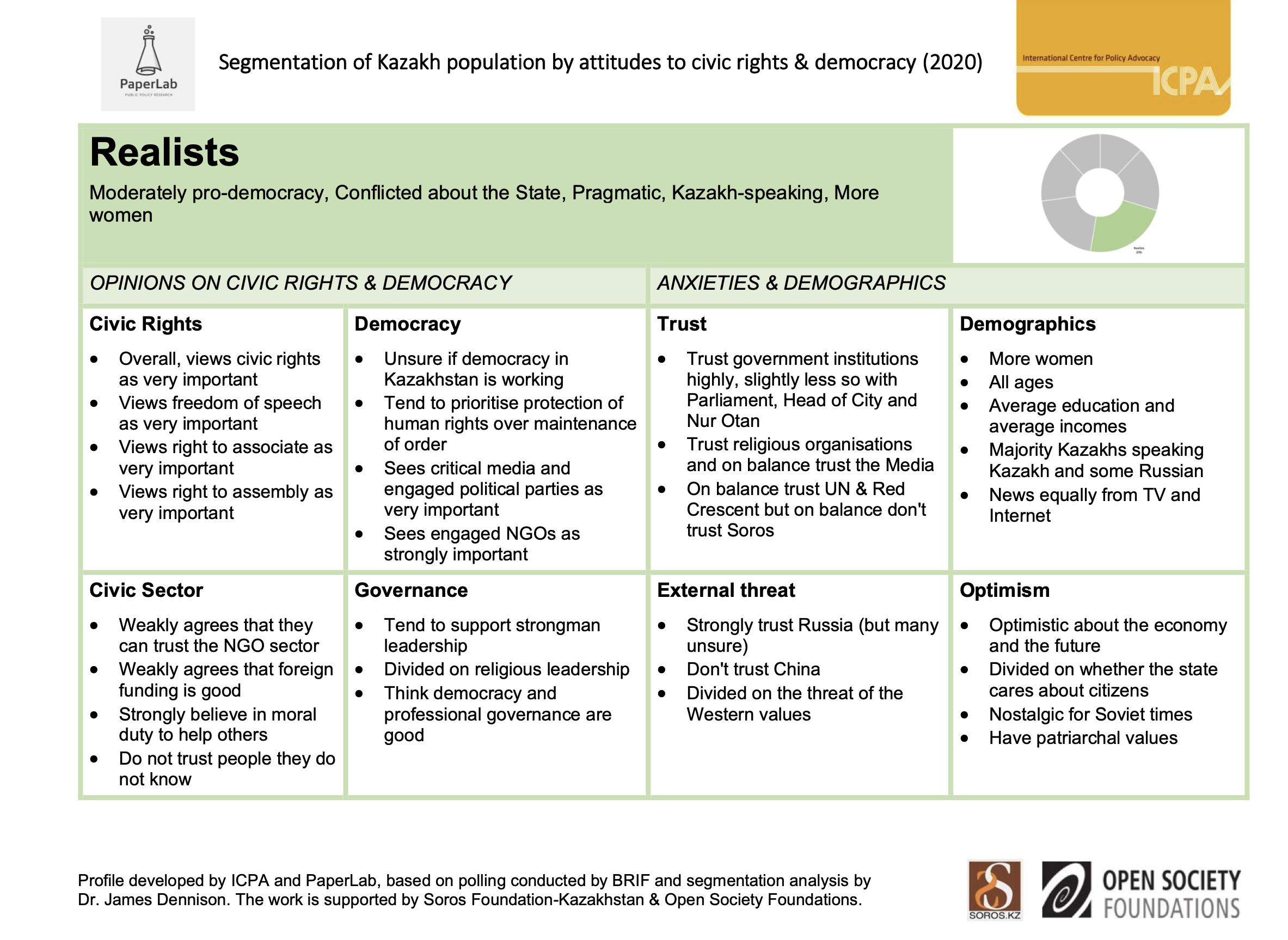

- Get access to or commission segmentation research to get a more nuanced and in-depth view of public attitudes: Having access to public opinion research which segments the public into groups based on similarity of attitude around democracy and civic action is key to understanding who to target, rather than having a generic and vague ‘general public’ or ‘majority’ as the stated target audience. This more granular view of public opinion, in turn, helps identify the value appeals that might work with them. If it’s not already available, ask funders to support such analysis as a crucial foundation for an evidence-grounded public advocacy effort. The resulting analysis can be used by many stakeholders once available, and committing to sharing and making such insights widely available among the sector is important. Below is an example of a summary profile of one of the middle segments from Kazakhstan, which was an important basis for the narrative development process:

Figure 5 – Profile of one of the moveable middle segments in Kazakhstan

See the segment profiles for all six segments of the Kazakh research.

- Personify your target audiences to help develop resonant messages: Don’t leave your target audiences as research subjects; instead, think of who you know that is part of this segment, for example someone in your family, workplace or neighbourhood. In our workshops, we ask campaigners to draw an example of the kind of person belonging to the target segment. For example, the drawing below of ‘Ainash Apa’ (‘Auntie Ainash’), belongs to the ‘Conflicted Optimist’ segment in Kazakhstan.

Figure 6 - Personification of the ‘Conflicted Optimist’ segment in Kazakhstan

These activities help to humanise your target middle audiences, and to understand their motivations and anxieties. This is a key step in developing messages that have a good chance of resonating with your target audience, and as one CSO participant in Kazakhstan reported, this tool helped to always think of their target audience as real people, in their families and communities. See our toolkit for the steps in building a full narrative change strategy, including these elements.

What you can get wrong

- Writing off the middle before you start, rather than focusing on understanding the segments: It is challenging to unpack and understand a segment of the public you may not agree with or even like very much. We see a tendency among progressive CSO people when observing focus groups with middle segments to harshly judge and bring a deficit view of those they’re observing. However, it’s so important to be open to learning about them, seeing their humanity, and even finding unexpected points of agreement between you. One of the Kazakh coalition partners we supported reflected on this in a helpful way: “There is a tendency to take their feedback in focus groups for example, and think ‘oh these folks are stupid’. But take the feedback seriously even if it’s not argued seriously. This is what your idea triggered – take that seriously!” To stay more open through this process, it may be useful to remember one of our narrative change keys: ‘Understanding does not equal agreement!’.

- 1More in Common have conducted attitude segmentation research on many issues including NGOs, democracy and civic rights. In partnership with the Kazakh think tank, PaperLab, we adopted this methodology in commissioning similar research in Kazakhstan, which is shown in the case box.

- 2Frank Sharry, America’s Voice

- 3MediaNet (2021) Azamatbol Campaign Facebook Page

- 4Kapronczay and Kertesz, Global Dialogues (2018) Dropping the defence: hopeful stories fight stigma in Hungary

- 5Lifeline (2022) Reanimating civil society: A Lifeline guide for Narrative Change

- 6Lifeline (2022) Reanimating civil society: A Lifeline guide for Narrative Change