Lesson 6 - Bring values to life through storytelling

Essence

Engaging storytelling is key to bringing the work of civil society to life for the general public around a set of shared values.

Insight

Stories are the connective tissue or bridge between your value appeal and the issue you want to discuss (as figure 7 in Lesson 5 shows). Values are the foundation of narrative change, but without illustration, they can remain quite vague and conceptual. The need to unpack values through stories is really clear during focus group discussions we run as part of the narrative development process. Strong, authentic storytelling plays a key role in making a value appeal accessible, striking and lays a foundation for the issue you want to discuss. Good storytelling humanises the issues you’re addressing, and in essence, brings your values to life.

In civic space campaigns, storytelling often illustrates the work of CSOs and how they respond to shared challenges and/or fulfil shared aspirations for the communities they serve. There are many ways to tell these stories, and the empirically-tested practice we support shows that having the real voices of CSO practitioners and those they serve works well in civic space storytelling – key components in warm and authentic storytelling approach. In many focus groups tests we’ve conducted, such stories with real people in recognisable communities overcoming shared challenges serves to soften the natural resistance of the group. Such stories also help the campaign pitch, call to action and slogans make sense.

Cases

- Kenya – Campaigners worked with Kenyan CSO leaders who had been accused of being ‘enemies of the state’ and organised for them to do social media interviews, taking questions from the public and telling their story to humanise them as fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, neighbours, colleagues with normal concerns, challenges and hopes. Hence, this more emotional type of storytelling served to reframe the discussion, rather than using a factual or defensive approach centred around negating the false accusations.

- Hungary – ‘HCLU is needed!’ campaign: Instead of getting caught up in the polarising back and forth of defamatory government attacks, the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) decided to talk about what they stood for: “by humanizing our staff…and clients. We first introduced our clients through personalized online stories that demonstrated that they are “one of us” and that human rights protect everyone. For instance, we featured an elderly woman’s story about why freedom of speech was important to her”2 .

This storytelling approach served to make the values and work of HCLU relatable and relevant for the target audiences, which are important factors for winning support for your cause.

See the Advocacy Cases Section 6 for more details and background on the cases.

Action

Nowadays, there are many good resources on effective storytelling for campaign work – the work of Marshall Ganz and Humans of New York have been particularly influential for our work3 . From our hands-on experience, four key principles to guide effective storytelling for civic space work are:

- Show, not tell: values need an affective/emotional response, not a cognitive one. So, it’s better to avoid the ‘talking head’ explanation to camera of CSO work; rather, it’s more effective to show the work in action in a dynamic and personal way.

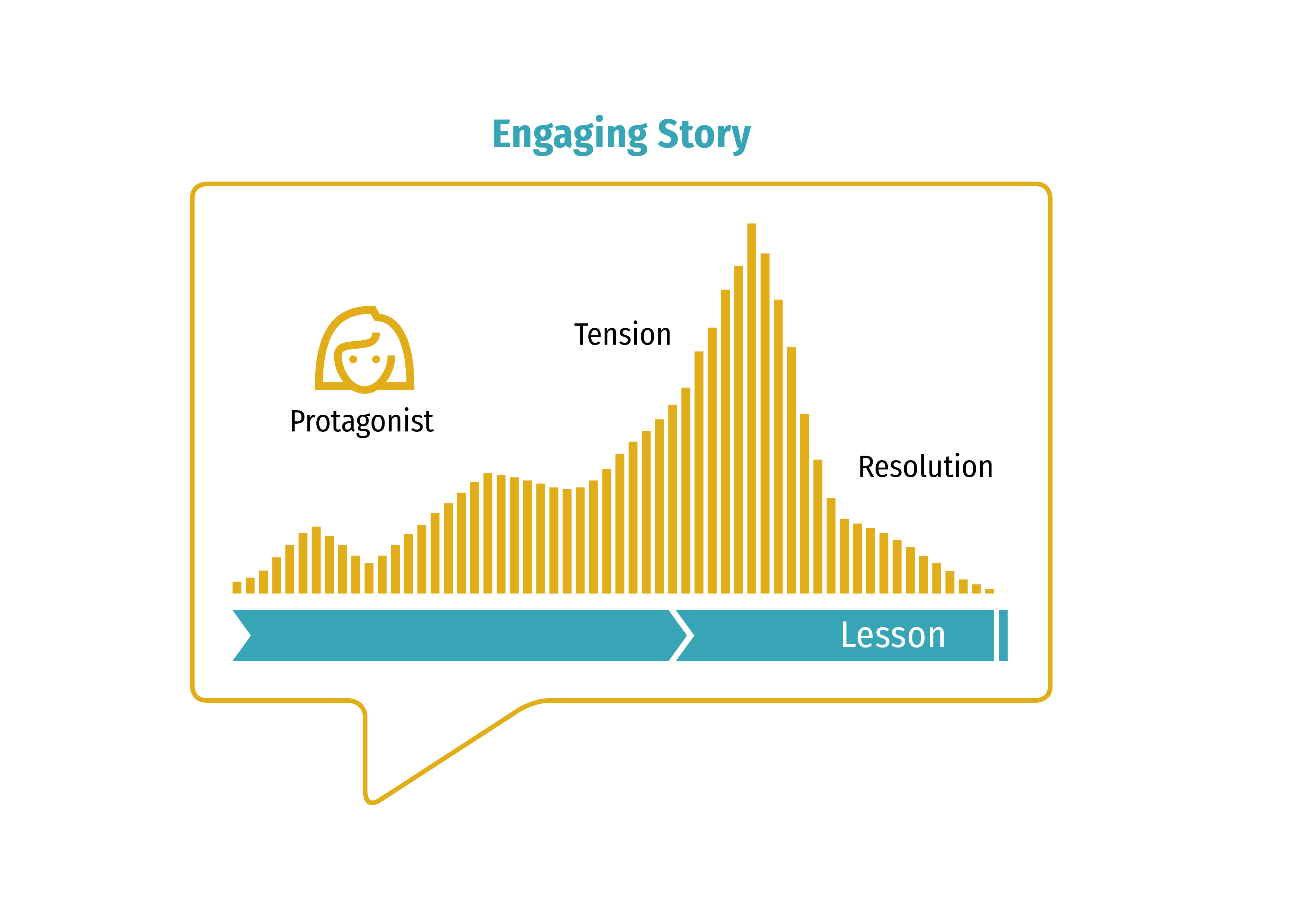

- Problem – Solution – Hope: Engaging stories need suspense. Having a protagonist face and then overcome a challenge – the aspect of tension as illustrated in Figure 9 – and then resolve the story to a hopeful future of shared aspirations works well to keep audiences engaged. The Assel video from the Kazakh #Azamatbol (#GoodCitizen) campaign is a good illustration of this movement.

Figure 9 – The elements of an engaging story

- Authentic 1st person voice: the people who actually overcame a challenge will always be the most convincing for the target audience, rather than their story being told second hand. Try to move beyond the facts of the story when interviewing protagonists; rather, seek to understand their hopes and fears through the experience, and share those insights in the story that’s made public. An important note: It’s paramount to respect that the extent to which protagonists want to share their story and this has to be determined with their full consent. The safety of protagonists must be maintained as the top priority.

- Balance resonance and dissonance: build the story with the right amount of resonance in shared values, and also dissonance in which something unexpected happens and works to get audiences to question and reconsider their current position on an issue. This then serves as the bridge to a discussion of your issues4 . Landing on this moment of what we call ‘constructive confusion’ is important in the process to shifting attitudes.

What you can get wrong

- Only focusing on your challenge, not on stories of shared challenges: CSO practitioners are trained to talk about their own motivations and the urgency of the issue they work on. While these are essential elements of a campaign story, more emphasis often needs to be placed on telling the ‘the story of us’5 , i.e. stories of experiences, challenges and goals shared by CSOs and their target audience.

- Having a lecturer voice on: As one of our Kazakh advocates put it: “if you come over as ‘talking like the state’ then no one will listen”. It’s important to avoid being too technical or in heavy educational mode; rather you need to find an everyday voice and it needs to be authentic.

- 1MediaNet (2021) Azamatbol Campaign Facebook Page

- 2Kapronczay and Kertesz, Global Dialogues (2018) Dropping the defence: hopeful stories fight stigma in Hungary

- 3For example: 1. Narrative Arts (2016) Marshall Ganz- Story of Self, Us, Now ; 2. Lauren Girardin (2021) https://storytelling.comnetwork.org/explore/127/5-storytelling-best-practices-at-the-heart-of-humans-of-new-york"target=“_blank”>5 Storytelling Best Practices at the Heart of Humans of New York

- 4ICPA (2018) Reframing Migration Narratives Toolkit: Core Lessons

- 5Narrative Arts (2016) Marshall Ganz- Story of Self, Us, Now