Section 2 - Why people adopt conspiracy thinking

At the core of our project is a very pervasive conspiracy theory called the ‘Great Replacement’, in which NGOs - especially those supporting migrants and refugees - are accused of being ‘traitors’ to the state1 . Therefore, it was very important to have a clear understanding of what drives belief in this kind of conspiracy thinking.

2.1 What is a conspiracy theory?

First, we need to recognise that conspiracies to secretly do something illegal or harmful happen and the initiative to find the evidence to uncover such plans is the positive motivating force behind investigative journalism and watchdogging. However, on the more negative side, it is specifically theorising a conspiracy without sufficient proof and aggressively presenting it as truth that is our focus2 . This harmful side of conspiracy theories have an established meta-narrative: nothing is as it seems, everything is connected, planned and fixed by a secret group of evil doers3 . Given the current level of the uptake of conspiracy thinking, it represents a serious threat to trust in institutions and democracy. With trust in institutions falling in Germany4 , finding practical steps to tackle the spread of conspiracy thinking could not be more important.

2.2 Why do people believe conspiracy theories?

There are important psychological explanations that help us to understand why people are prone to believing conspiracy theories. Conspiracy-driven stories of evil doers with an agenda seem to be very sticky for those seeking meaning and are said to fulfil some basic needs:

- An epistemic motive to explain complicated things in a simple way;

- An existential motive to feel in control;

- A social motive to feel good about being part of an ingroup who knows what’s “really” going on versus the ‘naïve’ general public5 .

These recognised psychological drivers inform the socio-economic patterns of those who tend be open to this kind of conspiracy thinking: those who find it difficult to deal with times of change or uncertainty. The names and demographics of the segments on the right in the More in Common 2019 study - the Detached, the Disillusioned and the Angry - are illustrative of such a mindset6

. And indeed, in our own survey in 2023, we found higher levels of conspiracy mindedness in these segments (See the 2nd column on page 2 of their profiles - Detached & Disillusioned). Antonio Amadeu Stiftung nicely bring to life the feeling of marginalisation held by these segments by explaining that those who readily take on conspiracy thinking are “people who previously felt isolated, overtaxed, helpless, excluded, patronised, commanded and ignored”, want to “have a ready solution to all problems” and “to find the culprits for one's own social misery”7

.

It is also worth noting the growing prevalence of conspiracy stories as a major narrative line for more and more fiction and documentaries to the point that the so-called “paranoid style” in viewing political motivation8

has become the “paranoid lifestyle”9

. So, as we have become more and more immersed in this story pattern, it becomes more accessible, sticky and for many, more believable.

2.3 Different levels of usage & belief

Maybe the most important finding from the literature for this project and confirmed in our focus groups was a finding that came from the anthropological study of conspiracy thinking10 . In this work, they found an important difference in the level of belief and usage of conspiracy arguments between what they call “conspiracy theorists” and “conspiracy talkers”. Theorists are hardcore believers who virtually always explain the world using the ‘nothing is at it seems’ meta-narrative, whereas there are many more people who are talkers, i.e. not nearly as committed, but without different explanations available, use the line of argument to provide a simple explanation and to be seen as part of the ingroup11 . In contrast to theorists, we found in our focus groups that talkers are also people who are happy to use a rational evidence-based explanation, if they have it to hand. As you will see in Section 5, this is a very important insight in this project, as our 2 target segments more or less cleanly break out along these lines, with the Detached acting more like talkers and the Disillusioned more like theorists, or as we prefer to call them ‘conspiracy thinkers’, i.e. they have very much embraced the theory for it to become the basis for their analysis of the world.

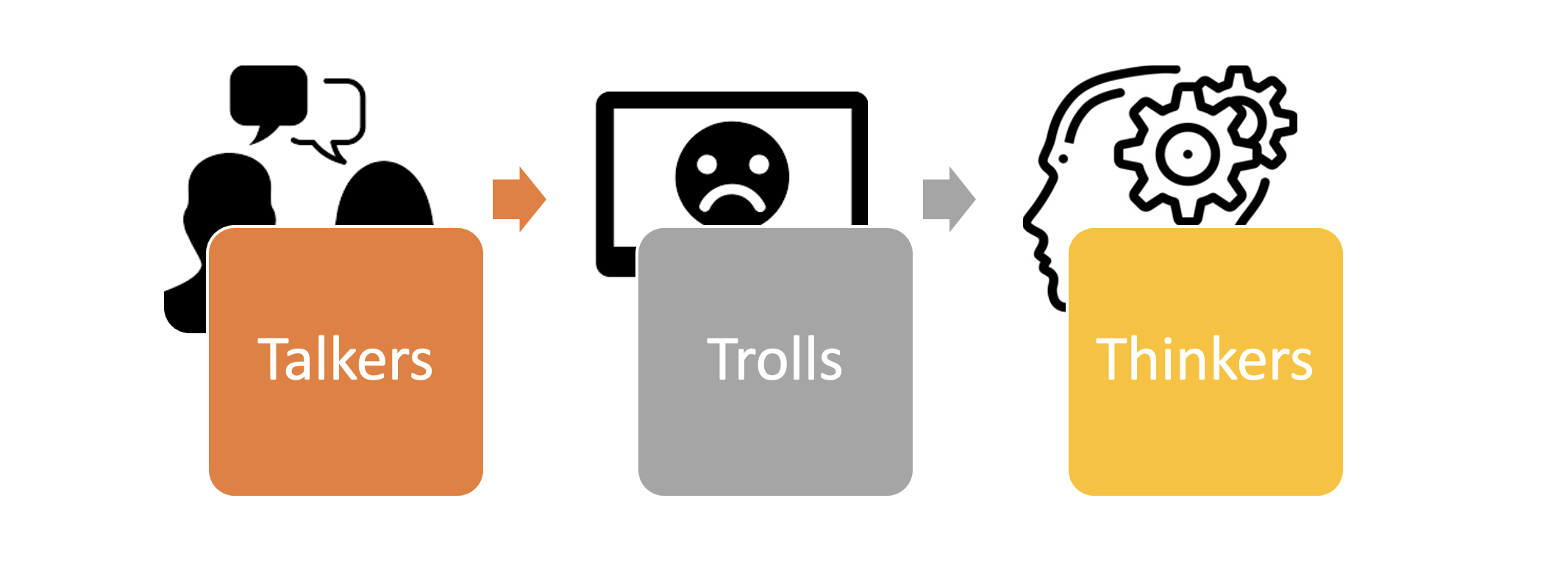

Figure 3: Different levels of belief/usage of conspiracy theories

In addition to thinkers and talkers, given the fact that much of the spread of conspiracy thinking happens online, we also thought it is useful add the 3rd category of ‘Trolls’. “Trolling is when someone posts or comments online to 'bait' people, which means deliberately provoking an argument or emotional reaction”12 and the troll we are focused on is one who maliciously spreads conspiracy thinking just to get a reaction/attention and to act as click-bait which drives traffic. So, while their level of belief is not clear, they are using conspiracy thinking in an instrumental way. This is a very important factor to consider in any attempt to reduce the expanding online presence of this kind of thinking.

<-- Section 1 - Introduction | Section 3 - Great Replacement -->

- 1Institute for Strategic Dialogue (2019) ‘The Great Replacement’: the violent consequences of mainstreamed extremism

- 2Lasar, Matthew/UC Santa Cruz (n.d.) Conspiracy Planet. Coursera Online Course.

- 3Butter, Michael & Peter Knight (2020) COST conversations with two experts on conspiracy theories. .

- 4Edelman Trust Barometer – Global & Germany – 2022, 2023, 2024.

- 5Douglas, Karen M. et al (2019) Understanding Conspiracy Theories. Advances in Political Psychology, Vol. 40, Suppl. 1, 2019.

- 6More in Common (2019) Die andere deutsche Teilung: Zustand und Zukunftsfähigkeit unserer Gesellschaft.

- 7Antonio Amadeu Stiftung (2015) "NO WORLD ORDER": How anti-Semitic conspiracy ideologies transfigure the world Wie antisemitische Verschwörungsideologien die Welt verklären.

- 8Hofstadter, R. J. (1964). The Paranoid Style in American Politics. Harper’s Magazine.

- 9Lasar, Matthew/UC Santa Cruz (n.d.) Conspiracy Planet. Coursera Online Course.

- 10Rabo, Annika interviewed in COMPACT (2020) “Part 4: How conspiracy theories spread” Expert guide to conspiracy theories. A podcast series on The Conversation’s Anthill.

- 11COMPACT (2020) Expert guide to conspiracy theories. A podcast series on The Conversation’s Anthill.

- 12eSafetyCommissioner/Australia (2024) Trolling.