Section 3 – Common Attack Narratives

As outlined in the previous introductory section on civic space (See Section 2), restrictions on civic space range from incremental (e.g. public defamation, heavy tax burdens, excessive bureaucracy) to radical (e.g. shutting down organisations, violent attacks, imprisonment), with all measures designed to cripple the sector. A set of narratives commonly used to attack and undermine trust in the sector are at the heart of preparing the ground for these kinds of restrictive actions on civic space.

This section details the common patterns of these dominant attack narratives based on an analysis of 31 cases from around the globe (See Section 6), mapping such narratives in different contexts, and key literature from the field1

. We have adapted and fleshed out the outline of the main narratives (detailed below in Table 1) with stakeholders directly affected by civic space issues in numerous trainings and presentations since 2017. To get a balanced perspective, we also recommend, in addition to understanding the negative attack narratives, conducting a mapping of the more positive narratives that exist around the discussion of civic rights and CSOs to find a way to ‘change the weather’. For more on this, see Lesson 2 in Section 4.

Tactics and purposes of attack narratives

Our work on analysing narrative tactics and mapping sets of narratives used for such attack purposes on CSOs, as well as the work of others, shows that a playbook on narrative tactics for aspiring authoritarians exists2

. With small adaptations for messaging that shape them in a culturally relevant way, the set of attack narratives are quite similar from country to country. It was an important realisation for us that there is ‘method in the madness’ around such attack narratives. Hence, a first step in empowering civil society to respond strategically and tactically (rather than just be in reactive mode) is understanding the nature and purpose of these common set of narratives attacking civic space. Having this insight also means that it is possible to design communications response strategies that inform action nationally and on a wider global level.

A useful way to understand the narrative attack strategy is that it aims to distract, divide and detach3

. More specifically:

- Distract – Putting civil society on the defensive so CSOs can’t continue to fulfil their everyday work;

- Divide - Separating ‘good’ CSOs (often community groups, churches, unions, sports clubs) from those targeted in attacks, e.g. human rights groups, watchdogs and think tanks/researchers. Those targeted are often focused on tackling corruption and violation of rights, and monitoring elections;

- Detach – Actively undermining public trust in the civil society sector.

Whether used individually or combined in a communications package, the set of narratives are used to justify some combination of the following set of actions targeting CSOs:

- Strict and burdensome reporting and auditing requirements;

- Laws to restrict access to or use of foreign funding and international banking;

- Aggressive, expensive and slow court procedures for those who infringe reporting guidelines;

- Revocation of CSO legal status;

- ‘Foreign Agents’ laws which force CSOs to label themselves in public as ‘traitors’;

- Closure of organisations;

- Arrest, detention and prosecution.

For example, the main line of narrative attack in Kazakhstan since 2015 frames CSOs as inefficient, wasteful, not transparent and not aligned with national priorities. The lesser lines that are used in this ‘communications package’ are focused on ‘Good’ versus ‘Bad’, with the ‘bad’ CSOs portrayed as foreign agents. This has led to a more incremental package of legal actions which started with very burdensome reporting and auditing requirements, restrictive tax laws which place obstacles on accessing foreign funding and working with foreign partners, and aggressive court actions for non-compliance that threaten suspension and shutdown4

. Most recently, in an intimidation and defamation effort, a list was compiled by state authorities of those receiving foreign funding, and this list was made public5

.

Dominant narratives attacking civil society

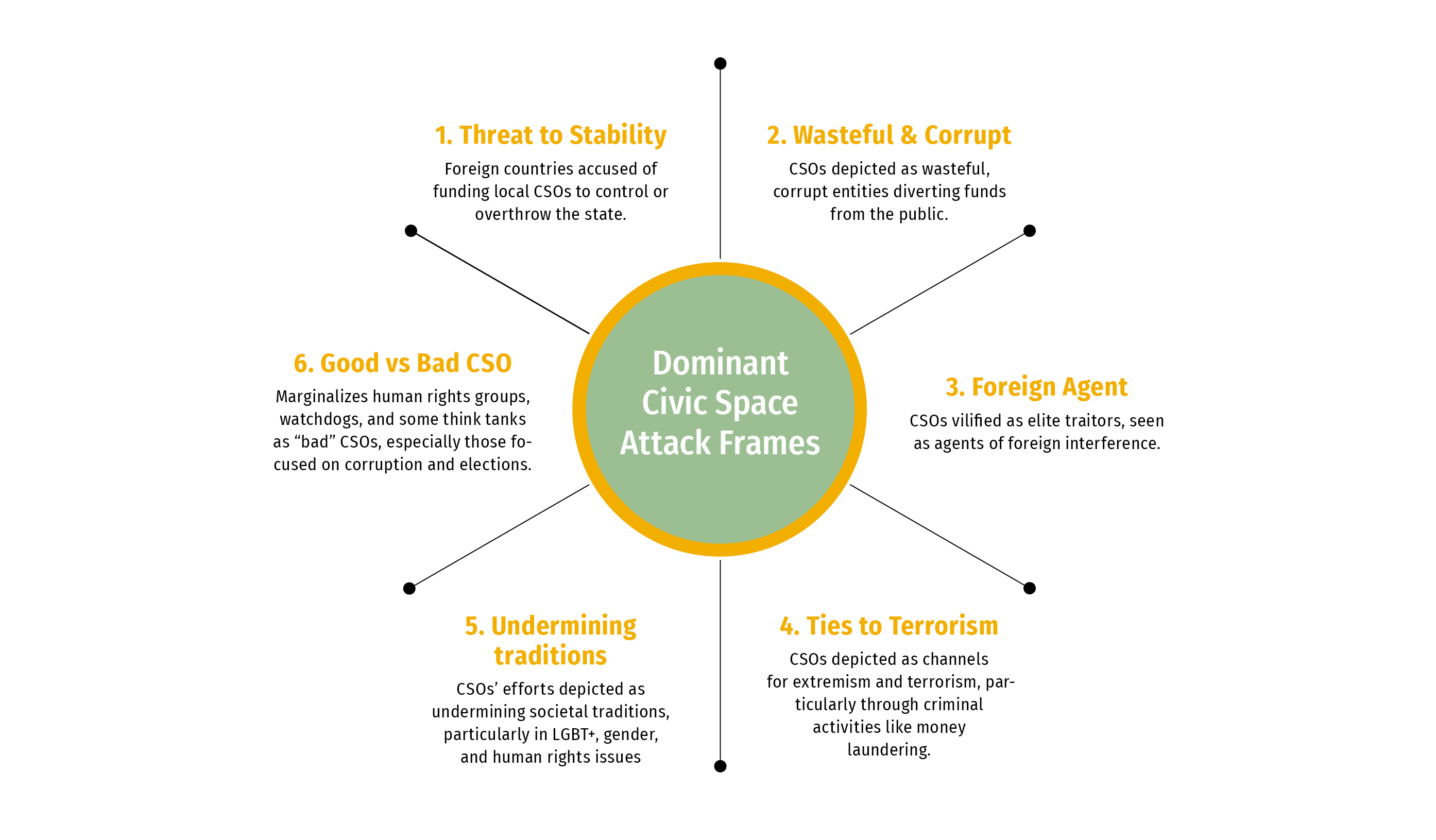

The following diagram provides an overview of the commonly used attack frames:

Figure 2 – Dominant Civic Space Attack Narratives

The table below provides a more detailed breakdown of each narrative (download PDF version). The order relates to the prevalence of usage in the global cases analysed. Apart from the ‘foreign agent’ narrative which is a term derived from the Russian 2012 law, we have named each narrative to capture the essence of the accusation and attack.

| Narrative | Explanation and Illustration | |

| 1. |

‘Threat to stability’ Present in 72% of cases analysed |

This narrative builds on old Cold War/imperialism frames to claim that some Western countries have a plan to meddle, control or even overthrow the state through foreign funding. Following this logic, these foreign actors and their local CSO partners are accused of representing a threat to stability. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, the so-called ‘Colour Revolutions’ are often cited as evidence for this narrative. It is commonly used in combination with the ‘Undermining Traditions’, ‘Foreign Agent’ and ‘Ties to Terrorism’ frames. |

| 2. | ‘Wasteful & Corrupt’ Present in 61% of cases analysed Examples: Ecuador, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Nepal |

In this narrative, CSOs are portrayed as inefficient, wasters of money who take funding from the ‘real’ people and are not contributing to national plans or priorities. In addition, the frame accuses CSOs of not being transparent about what they do with funds, and are thereby, portrayed as corrupt. In Kazakhstan, this frame is captured in the accusation that CSOs are “grant eaters” and this is used to justify heavily increased government oversight under the guise of holding CSOs accountable. It is commonly used in combination with the ‘Threat to Stability’ and ‘Undermining Traditions’ frames. |

| 3. | ‘Foreign Agent’ Present in 44% of cases analysed Examples: Hungary, Kenya, Malaysia |

In this narrative, CSOs are portrayed and vilified as corrupt, entitled elite who act as partners of meddling foreign entities. This ‘traitor’ motif often builds on ideas of a big globalist conspiracy at play. Depending on the culture, this narrative often links to antisemitism (e.g. how George Soros is depicted by many states) or other figures who have become historical bogeymen. Not surprisingly, this narrative is directly tied to so-called ‘foreign agent’ laws which force CSOs to mark themselves in public as traitors, which serves to undermine their reputation. This often leads to intimidation, hate speech and even violence against CSOs. It is commonly used in combination with the ‘Threat to Stability’ and ‘Undermining Traditions’ frames. |

| 4. | ‘Ties to terrorism’ Present in 39% of cases analysed Examples: Mexico, Nigeria, Kyrgyzstan |

In this narrative, CSOs are framed as a conduit for extremism and terrorism, especially in the accusation of facilitating criminality and corruption through money laundering. Post 9/11, this narrative has led to many restrictions on banking and access to funding for CSOs, especially from foreign sources6 . It is commonly used in combination with the ‘Threat to Stability’ frame. |

| 5. | ‘Undermining Traditions’ Present in 28% of cases analysed Examples: Nepal, Kazakhstan, Uganda |

This narrative frames the work of CSOs as a threat to the state-defined fabric of societal traditions - often focused on the family - and involves heavy criticism of LGBT+ and gender issues, human rights, secularism, and even democracy agendas. This narrative finds resonance among traditionalists and has driven a global right-wing religious coalition seeking to protect “the family”7 . It is commonly used in combination with the ‘Threat to Stability’ and ‘Foreign Agent’ frames. |

| 6. | ‘Good’ vs ‘Bad’ CSOs Present in 11% of cases analysed Examples: Kazakhstan, Hungary |

This frame seeks to define and marginalise human rights groups, watchdogs and certain think tanks (often focused on tackling corruption and violation of rights, and monitoring elections) as ‘bad’. It also contrasts them with the perceived ‘good’ CSOs, such as community groups, football associations, unions, churches, and those who toe the political line – often GONGOs8

. This frame is commonly used to justify funding of CSOs who are more in line with government, i.e. GONGOs. While the good/bad wording is not literally used in many cases, it is often implied behind the vilification of CSOs as traitors, undermining stability and not supporting the national project. It is often used in combination with any of the other frames used to explain and portray the “bad” CSOs. |

Table 1 – Detailed breakdown of dominant civic space attack narratives (download PDF version)

It is worth noting that many of these narratives are grounded in conspiracy thinking and theories, for example, the ‘Great Replacement’ theory9 . We are currently experimenting through a project in Germany - Proactive Protection – Inoculating against Extremist Conspiracy Narratives towards NGOs -to change the public narrative around CSOs who come under attack from those pushing conspiracy thinking and narratives.

<-- Section 2 - Overview | Section 4 - 10 Lessons -->

- 1Ariadne (2016) Challenging the Closing Space for Civil Society: A practical starting point for funders; Carothers, Thomas & Saskia Brechenmacher (2014) Closing Space: Democracy And Human Rights Support Under Fire. Carnegie Endowment For International Peace; Freedom House (2017) Breaking Down Democracy: Goals, Strategies, and Methods of Modern Authoritarians; Fundamental Rights Agency (2021) Protecting civic space in the EU; International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law (2018) Effective Donor Responses to the Challenge of Closing Civic Space; Israel Butler, Liberties (2021) How to talk about civic space: a guide for progressive civil society facing smear campaigns; Lifeline (2022) Reanimating civil society: A Lifeline guide for Narrative Change; OECD (2022) The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment With International Standards And Guidance.

- 2Freedom House (2017) Breaking Down Democracy: Goals, Strategies, and Methods of Modern Authoritarians

- 3Transparency and Accountability Initiative (2017) Distract, Divide, Detach: Using Transparency and Accountability to Justify Regulation of Civil Society Organizations

- 4ICNL (2024) Kazakhstan Monitor

- 5The Diplomat (2023) Kazakhstan Publishes List of Entities and Individuals Receiving Foreign Funding: When is a list not just a list?

- 6Including international banking oversight procedures like: The Financial Action Task Force (2024) What we do?

- 7For example, World Congress of Families (2019) Verona - The Wind of Change: Europe and the Global Pro-Family Movement About the Congress

- 8“A government-organized non-governmental organization (GONGO) is a non-governmental organization that was set up or sponsored by a government in order to further its political interests and mimic the civic groups and civil society at home, or promote its international or geopolitical interests abroad”, Wikipedia (2024).

- 9“Proponents of the so-called ‘Great Replacement’ theory argue that white European populations are being deliberately replaced at an ethnic and cultural level through migration and the growth of minority communities”, Institute for Strategic Dialogue (2024) The Great Replacement