Chapter 2. Narrative change as an advocacy approach

The #KommMit pilot adopts a value-based, narrative change approach to advocate for diversity and social cohesion. As this approach is not yet widely used and may seem quite abstract, this chapter situates the toolbox and clarifies the basics. So, in this chapter, you will gain insight into:

- the fundamentals of narrative-change advocacy;

- the merits of taking on a narrative change approach.

At the end of the chapter, we provide a checklist to help you consider narrative change as an approach to add to your advocacy toolbox.

2.1 What is narrative-change advocacy?

A narrative-change advocacy approach is built on the premise that in emotionally-charged and often polarised discussions such as the debate on migration, the values, concerns and emotional investment of stakeholders become an important gateway to engagement and constructive dialogue. Members of the public in such debates tend to get quite attached to one of the influential stories or frames in the public debate which act like a GPS in how they react1

, telling them what the problem is, what the solutions are, and who are the good and bad guys. The aim in this approach is to reframe the debate away from the well-worn pro- and anti-positions and frames fought out in the public and political space, and reduce anxiety enough to get often sceptical public audiences into a constructive discussion on the issue. In this way, public audiences become more open to changing their attitudes and previously held positions on an issue. And there is tried and tested evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach2

.

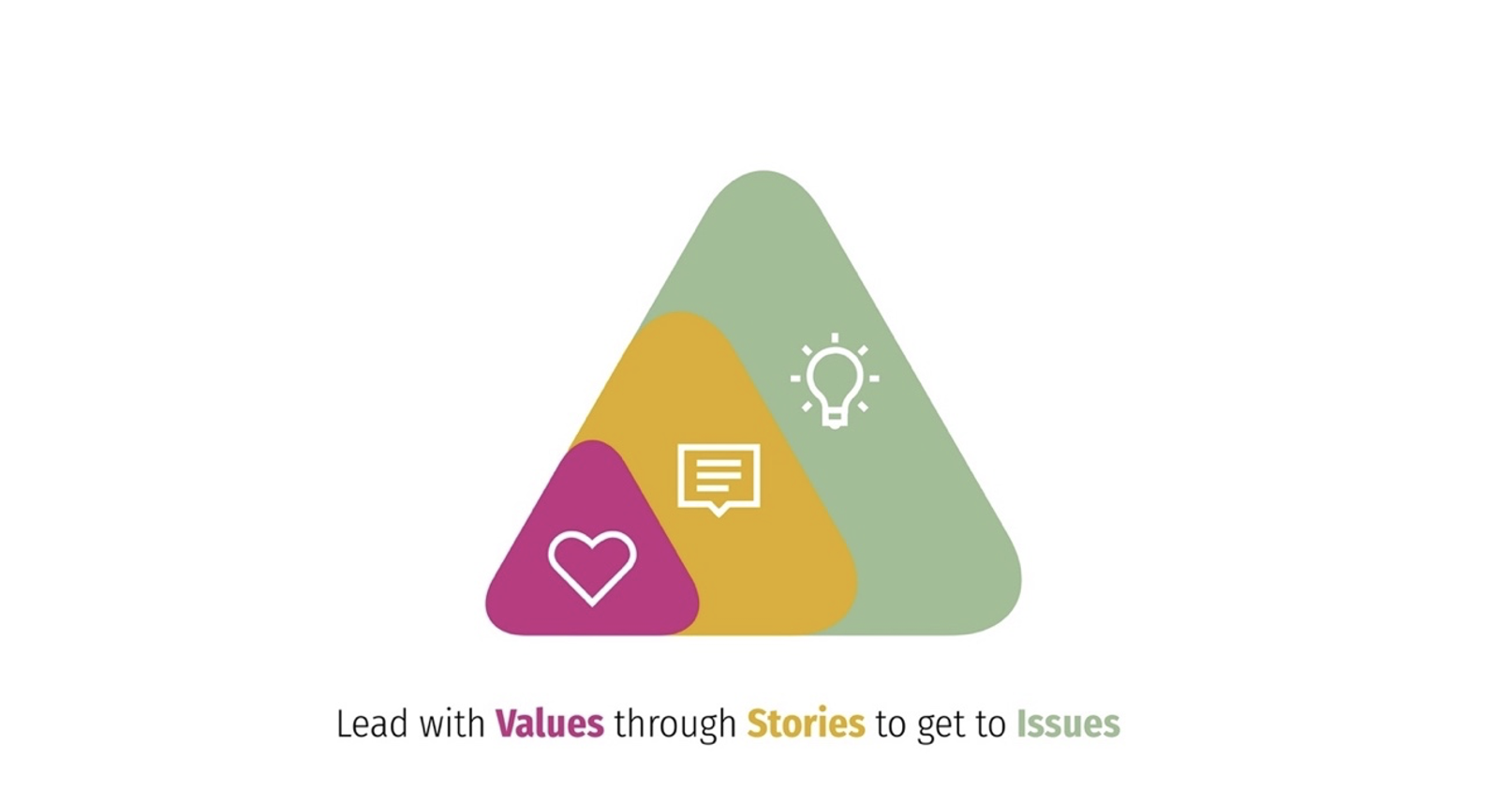

More specifically, a narrative change approach focuses on the emotional, engaging pathos, telling personal stories of experience, striving to create warm feelings that engage the audience through establishing common ground with them. Once you have the audience’s attention and interest, the focus is then on challenging the assumptions they make. All of this serves as the basis to open a constructive conversation between people whose opinions differ. Following Marshall Ganz3

, narrative change starts by appealing to the heart and then opens a discussion about the issues and facts (an appeal to the head) with the aim to move people more to your side, or at least, to reduce anxiety in the discussion enough to inoculate them against more right wing populist positions.

The key dimensions of narrative change are synopsised in Table 1 below, as well as what does not come under the rubric of this approach:

| What Narrative Change is ✅ | What Narrative Change is not ❌ |

| Leading with values and authentic stories | Leading with the issues, facts, and rights |

| An opening to a constructive conversation based on shared values and/or shared experiences | Magic words that can instantly change attitudes |

| A compliment to more facts and rights-driven advocacy | A replacement for facts and rights-driven advocacy |

| A pragmatic solution to win back the middle ground in a polarising debate | Giving up on your principles or denying a power/rights-based analysis |

| An emotionally smart way to have difficult conversations with sceptics | A way to avoid confronting people about their discriminatory views |

| Finding overlapping values as an authentic starting point to open a conversation | Trying to please the audience to convince them |

| Expansion of your advocacy toolbox that compliments the messaging to your supporter base | A way to lose your existing supporter base |

Table 1: Defining key dimensions of narrative change (ICPA 2024)

2.2 Why adopt a narrative change approach?

During the last decade, there has been growing frustration and anger among progressive CSOs at the dominance and mainstreaming of anti-immigrant narratives in Europe, which had previously been the preserve of the far-right. Many are also feeling a sense of helplessness as they experience that their usual advocacy approaches (e.g. evidence-driven advocacy) have now become less effective in building back public support in the polarised narrative landscape on migration and integration.

In putting forward a pragmatic, ethical, value-based narrative approach, we ask CSOs to consider the following six factors which convinced us about the merits of this approach:

Changing attitudes is not just about facts, it’s also clearly about values and emotions.

All the research conducted in this area comes to the same conclusion: humans first line of processing political debates is emotional, or more specifically, we tend to be open to proposals that are framed in values that are important to us4

. The opposite is also true: we close down, ignore or even react angrily to proposals that make no connection to or run counter to our values (even when such proposals are backed up by solid evidence!). So, effective communication with the goal of changing attitudes is never just about facts on the issue; rather, finding value appeals that mobilise and open the door to a constructive debate with various audiences is key. A value-led narrative change approach doesn’t ignore the facts and analysis; instead it’s about sequencing the message in an emotionally-smart way, so that sceptical public audiences will come to the table and be open to having a debate on often polarising issues. These steps are illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 2: The key steps in a value-based campaigning approach (ICPA)

In summary, it would be unproductive to ignore the realities of how human brains process information: narrative change and strategic communications seek to more consciously and deliberately recognise what the brain does by default anyway5

.

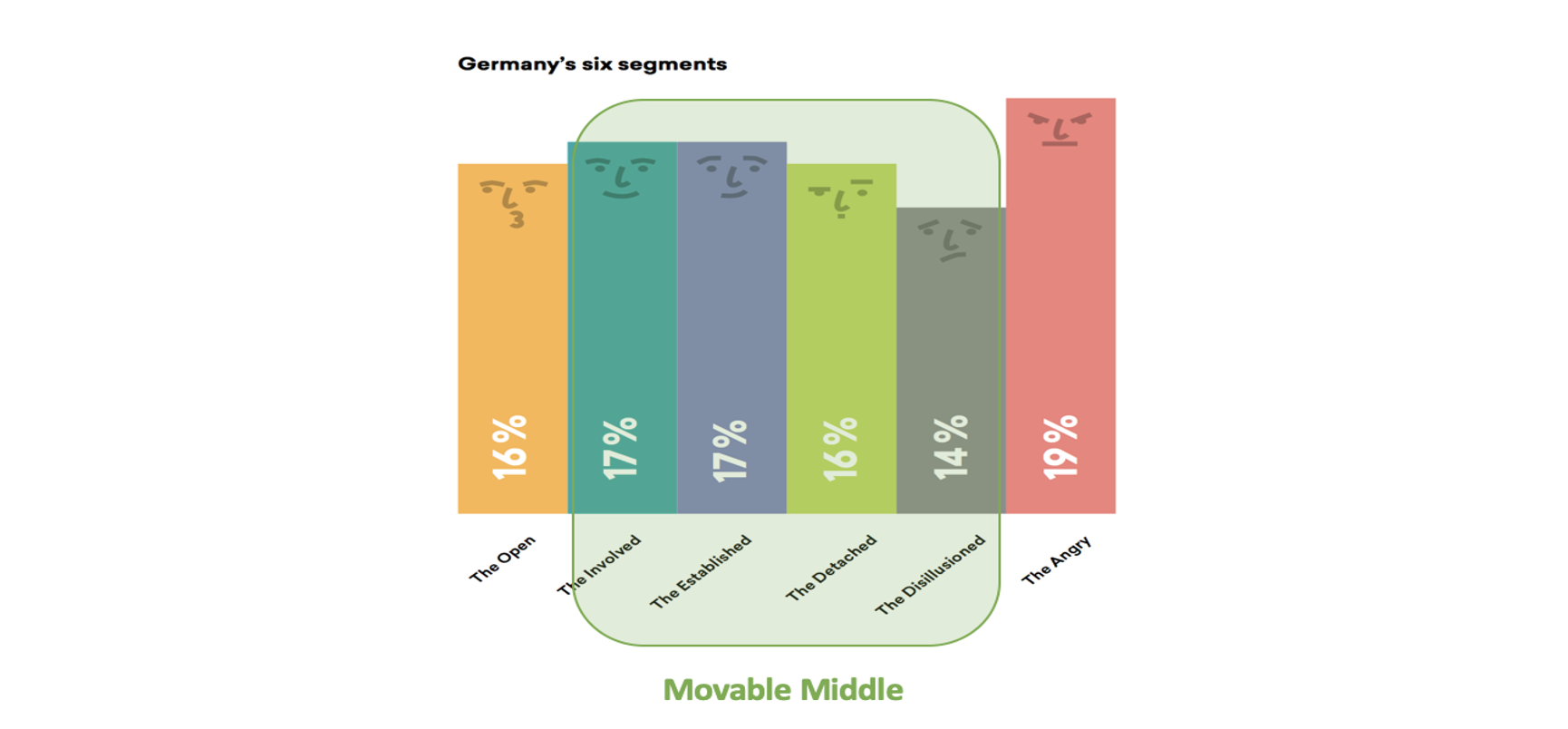

60%-70% of the public are movable in this debate, and currently represent a hugely untapped potential.

Many advocates working on different societal issues tend to consider the public in debates as broadly divided into supporters and opponents. However, in-depth (and repeated) segmentation and polling research on attitudes to societal issues (including migration) in Europe over the last decade clearly show that around 60% to 70% of the public are in the so-called ‘movable middle’, including in Germany, as illustrated in Figure 3 below. As a group, the movable middle are not so involved or engaged in issues and often hold conflicting views. However, as the #KommMit pilot narrative change project detailed in this toolbox and much previous campaigning experience shows, it is possible to change their minds, i.e. they are movable or winnable. If the goal is to shift the balance of the broader public debate and win back the centre ground, then the untapped potential of this middle group is key.

Figure 3: The movable middle in Germany (adapted from research by More in Common 20196

)

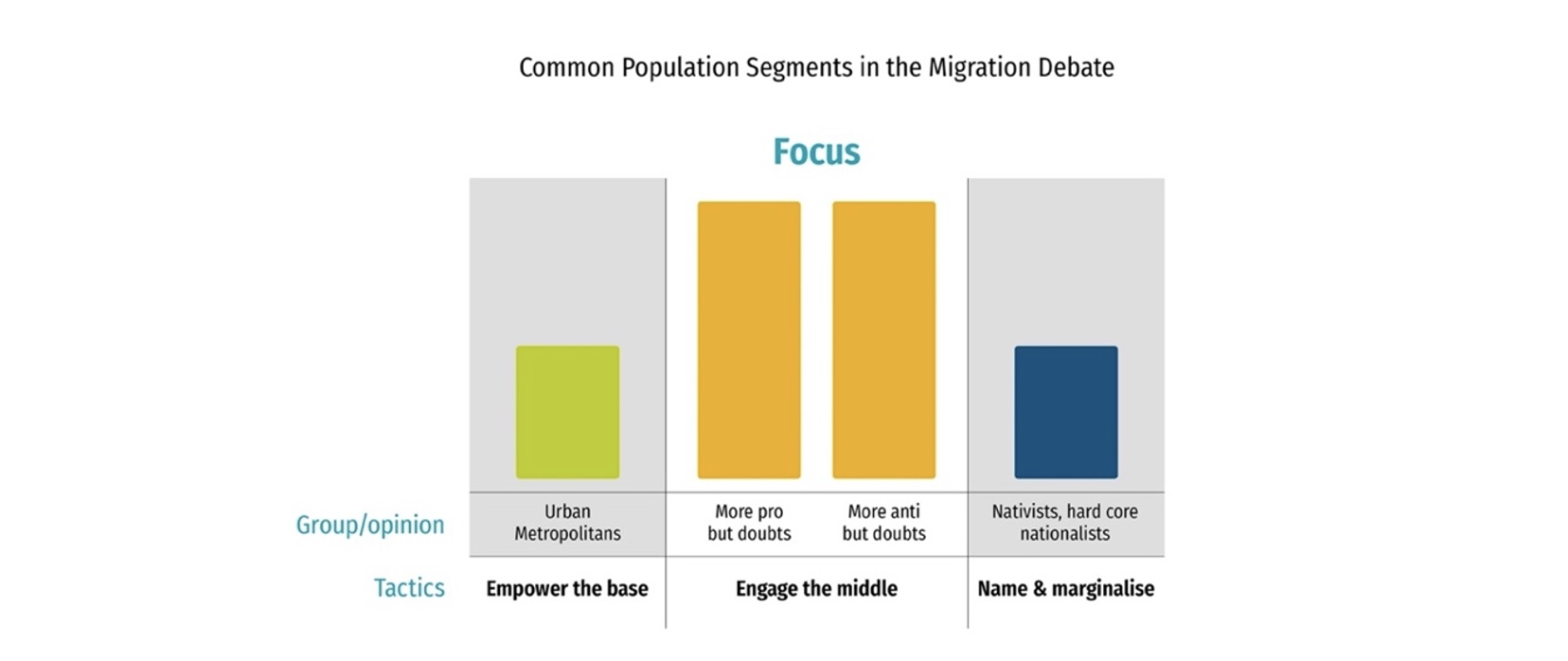

Engaging the middle doesn’t mean losing your supporter group.

Engaging the middle doesn’t mean you stop mobilising your supporter base: this a case of “both/and, not either/or”7

. In tactical terms, advocates in the broader social movement need to focus on BOTH building the base of supporters AND engaging the middle in order to achieve the movement’s social change goal. The following diagram provides a snapshot of the comprehensive and complementary strategic communications tactics for supporters, middle and opponents:

Figure 4: Targeting the movable middle as one tactic in a comprehensive strategic communications strategy

While this middle work is challenging and is not for everybody, it is an essential part of a progressive movement’s overall narrative and policy advocacy strategy. An insight from the RESET project: from the broad spectrum of CSOs we supported from the CLAIM Allianz, the ones on the ground who already engage in communities with middle groups at various levels as a target group were more immediately interested in taking on this middle work. This middle-oriented focus resonated with them, as this is already their everyday challenge.

Political agreement is made from overlapping consensus.

Having developed and tested multiple campaigns targeting the broad public over the last decade on the migration issue in Germany and Europe and knowing that 60% are really not that engaged or involved in the issue (i.e. the movable middle), the idea that agreement on the issue will be reached by finding ‘overlapping consensus’ is a pragmatic political reality. This means that agreement will be built from a variety of public groups, each of which will have different reasons for their decision to support the agenda. See the work of the political philosopher, John Rawls for more on this8

. For example, in Germany, the public can hold positive attitudes about migration and integration for a wide variety of reasons, e.g. they support a diverse society, think the economy needs migration, have a humanitarian perspective, and/or want Germany to be a country that provides asylum for people in need. Recent progressive victories in Europe have been won by working from this more pragmatic overlapping consensus understanding. For example, a huge turning point for marriage equality campaigners in Ireland before 2015 was a challenge posed by an experienced campaigner, who asked: ‘Do you want to win an argument or a referendum?’ Of course, the answer was a referendum and in 2015 they did so by engaging and mobilising the public around the variety of issues, narratives and emotional appeals needed to get over the line9

.

Understanding does not equal agreement.

Some advocates have concerns about campaigning to the middle because members of the middle may hold racist, sexist, and/or anti-democratic views and advocates feel uncomfortable with the idea of empathising and finding a shared value space with them. The first point to clarify is that digging into the research and trying to understand their positions is not a bridge to accepting their positions. Rather, this is a strategic need towards finding a starting point from which you can have a constructive conversation and then, challenge them.

Secondly, in a narrative change approach, the idea is not to start a conversation to please the middle, but to find shared values that are also authentic to you and your organisation, network or community. When working on the #KommMit pilot, for example, the starting point for engaging the middle focused on unifying values around social cohesion, e.g. community, interdependence, participation, intergenerational future. Equally important, the coalition running the pilot was not happy to build a campaign based on the economic ‘utility’ (Nutzbarkeit) argument for migration and, hence, were not open to using that value appeal. So, the overall idea is to find entry points that can serve as a unifying starting point, which then provide the chance to have the difficult conversation.

The key to an ethical narrative change approach is transparency and commitment to having the difficult conversations.

Some people challenge the approach saying it is too soft and smacks of political manipulation. However, we know from extensive practical experience that there is an ethical way to adopt this communications approach: firstly, it is important to be transparent with your network or community from the start that you are taking a value-based approach because you think this is what is needed; and secondly, secure commitment to having the issue and facts-based conversation once you open the space with value appeals. So, taking this softer approach does not mean you will avoid the difficult conversations (around the issues, problems, facts, and analysis that advocates really want to talk about); rather, it means you will be able to have conversations in a more constructive manner after building a space for civil engagement. Only then, is there a real chance of the audience changing their minds.

- Key insights – ICPA (2018) Keys to reframing the migration debate

- Narrative Change – ICPA (2018) Reframing Migration Narratives Toolkit

- Strategic Communications – ICPA (2023) Strategic Communications Knowledge Base

2.3 Fit of narrative change to your advocacy work

- What are your usual advocacy approaches and tactics?

- What successes have you achieved? What challenges do you face?

- What are your current big picture advocacy priorities and ambitions? Could a narrative change approach support this work?

- What is your experience communicating with more sceptical target audiences? How effective have your tactics been so far?

- Could a methodology that starts with a softer, values focus and leads to constructive dialogue fit the DNA of your organisation?

- 1Frameworks Institute (2023) Reframing the conversation about child and adolescent vaccinations

- 2Frameworks Institute (2024) Framing 101 ; British Future (2014) How to talk about immigration ; ICPA (2023) #KommMit pilot narrative change project: A value-based storytelling approach shifts attitudes towards Muslims in Germany .

- 3Marshall Ganz (2011) Public Narrative, Collective Action and Power.

- 4ICPA (2018) Understanding the power of frames.

- 5Davidson/Open Society Foundations (2018) Narrative Change and Open Society Public Health Program.

- 6More in Common (2019) Die andere deutsche Teilung: Zustand und Zukunftsfähigkeit unserer Gesellschaft.

- 7Frank Sharry, America’s Voice

- 8Cambridge University Press (2014) The Cambridge Rawls Lexicon: Overlapping Consensus .

- 9Ailbhe Smith quoted on 100 Campaigns that Changed the World Podcast (2023).