Section 2 – Overview of Shrinking Civic Space

With the rise of populism and democratic backsliding in recent times1 , attempts to shrink the space for civic action of civil society organisations (CSOs) are spreading at a worrying pace2 . To frame this resource, it’s important to explain our understanding of the term “civic space” and also why it needs protection in a healthy and thriving democracy. In addition, this section also breaks down how civic space restrictions are often introduced and the common responses of CSOs and their allies to fight them.

What is civic space and why does it matter?

The global civil society alliance, Civicus, provides a very useful definition that gets to the heart of the matter:

To break this out to a more basic rights definition, civic space is concerned with the protection of the following three rights for civil society:

- Freedom of Association – the right to form or participate in a group intended to voice concerns and promote certain interests and values, e.g. in NGOs, political parties, unions or associations.

- Freedom of Assembly – the right for people meet in public or private and voice their opinions on issues of public concern, e.g. in meetings, demonstrations, events or strikes.

- Freedom of Expression – the right for people to hold and share their opinions on issues without fear of sanction or reprisal from the state. The discussion around this right is often focused on freedom of expression in the media and social media platforms.

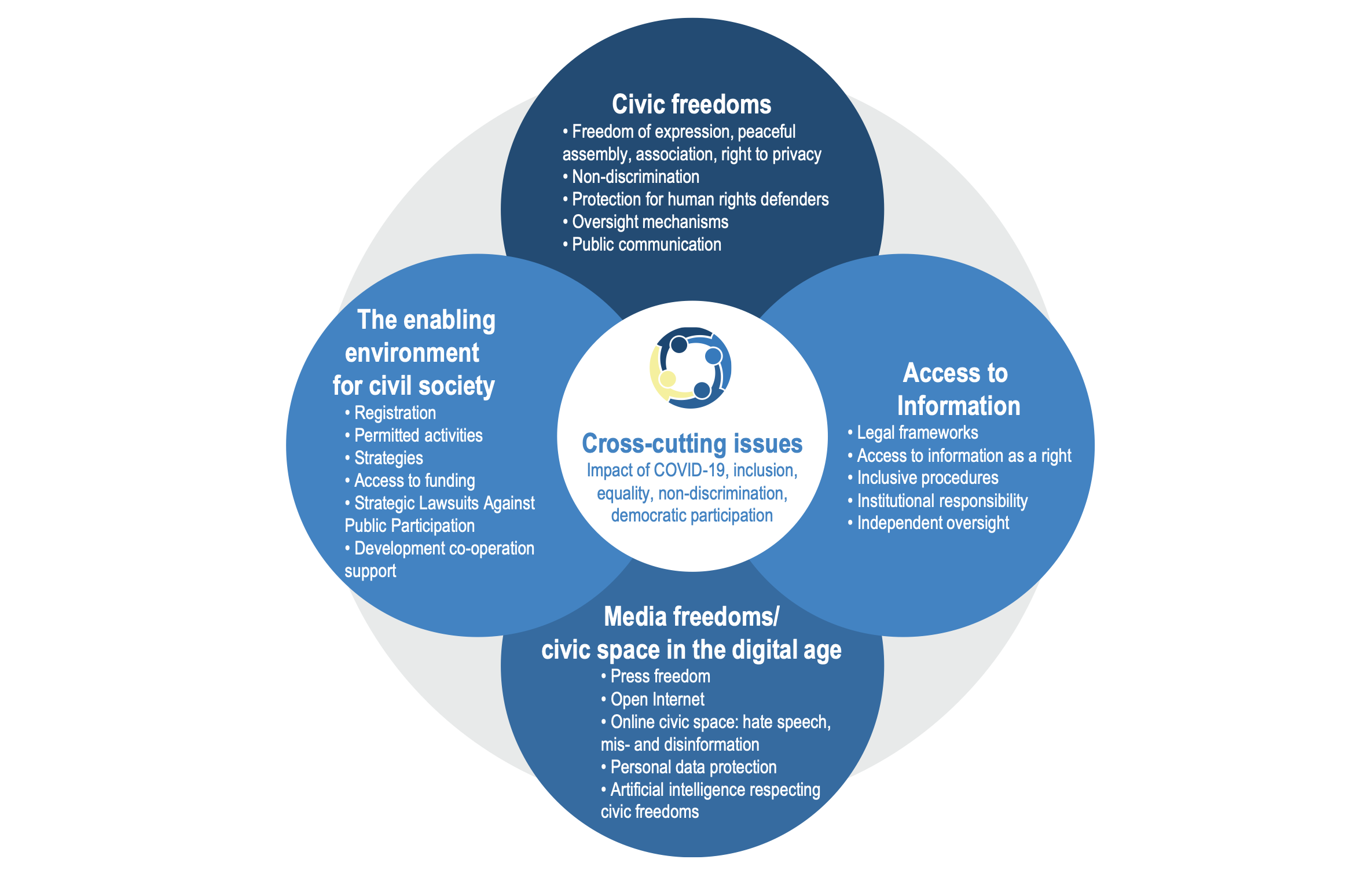

A recent report by the OECD incorporates these three rights within four practical dimensions that outline how a healthy civic space can be maintained: civic freedoms; the enabling environment for civil society; access to information; and media freedoms/civic space in the digital age (See Figure 1 below). Under each of these dimensions, they then breakdown the important aspects of policy, law and enabling environment that are needed. However, these aspects are also used as the entry points to restrict civic space, e.g. legal frameworks, access to funding, open internet.

Figure 1: The dimensions of civic space (OECD 2022)4

For many in the civil society sector, their everyday concerns are understandably focused on the constituency they represent, the issues they work on, as well as organisational growth and sustainability. But civic space rights are the foundations of a CSO’s institutional house, and like everyone who lives in a house, you focus on the condition and upkeep of the parts of the house and garden above ground, and assume that the foundations stay secure. Unfortunately, it is exactly these foundations that are under attack when civic space shrinks and therefore, effective responses need to be a concern for all who are directly involved and for those who value the role of civil society (also known as the 3rd sector) in any democracy. The danger is that the sector will eventually crumble, as restriction after restriction and attack after attack knocks the house down from the foundations.

What are the range of restrictions on civic rights that shrink space?

While a long history of attempts to restrict and obstruct civic space exists, the most well-known attack on civic space in this era is the ‘Foreign Agents’ law introduced in Russia in 2012. Although there are variations, it normally involves being declared a ‘foreign agent’ by the Ministry of Justice, then having to label your website and all activities as those conducted by a ‘foreign agent’, as well as registration, burdensome reporting and aggressive court oversight that can include civil and criminal penalties. This is an example of a more radical and aggressive measure with the intention to silence and basically, cease the operation of targeted civil society actors who may be critical of the government (e.g. human rights NGOs) in a short time frame5

. This is a model that other countries have also tried to follow, e.g. Kyrgyzstan.

More incremental approaches are ones that place excessive bureaucratic and tax burdens on CSOs and aggressively litigate non-compliance, restrict access to funding, and in parallel, actively seek to undermine the reputation of the sector in public. The aim of these incremental attacks, which have been on the increase in recent years - for example, in Hungary and Kazakhstan - is a long-term slow squeeze that significantly hampers the work of the sector in fulfilling its mission and creates a ‘chilling-effect’ that often leads to self-censorship6

.

Whether the restrictive approach employed is incremental or more aggressive, a common tactic deployed to undermine trust in civil society is the spread of defamatory, intimidating and vilifying narratives about the sector as a whole, targeted CSOs and/or even specific individuals from the sector. See our detailed map of the narratives commonly used to attack CSOs in Section 3.

What are common responses to attacks on civic rights?

While important actors have recognised this issue and provide their own prescriptions7 , a very useful overview of the responses of the sector when civic rights come under attack is provided by Ariadne funders network8 , with responses usually including a combination of the following levers:

- Legal and policy/political responses – e.g. strategic litigation and working with supportive political factions in parliaments

- Evidence-based advocacy – e.g. elaborating the quantitative and qualitative difference/contribution that CSOs make in service provision, such as health care or social services

- Coalition building – e.g. gaining the support of organisations with large constituencies like church groups, private sector and community associations

- Diplomatic and international organisation pressure based on commitments made to democratic standards – e.g. working with embassies to make public statements on commitments made to advance democracy, such as in the Sustainable Development Goals.

- A business case for the sector – e.g. advocating on the amount of employment provided, investment generated and tax paid by the sector.

- Publicly-focused narrative campaigning work – e.g. countering attack narratives and/or running public campaigns to build trust in the sector based on showing how CSOs are key to delivering on unifying values and aspirations of the state.

In the 31 cases we directly researched and/or analysed in the development of this resource (See Section 6), some combination of these levers has been used in all cases and in some, proved successful in pushing back on proposed legal changes designed to shrink civic space.

Need to consider a proactive response

What is striking about the cases we have examined is the more reactionary nature of the responses, i.e. it takes an impending civic space legal change that poses an existential challenge for CSOs to come together and act in response. This is understandable for the reasons stated above, but it is evident that such reactive tactics alone are not proving effective as the sole measure to halt the shrinking of civic space.

Shrinking civic space is a trend that is spreading among populist leaders globally9

and even in countries that have succeeded in preventing previous shrinking space initiatives, these threats persist (e.g. in Kenya and Kyrgyzstan). Therefore, there really is a need to invest in proactive approaches that aims to safeguard the sector from the initiation of these attacks. In this resource, we share insight into what works in positively shifting the narrative among the broader public – so-called ‘movable middle’ audiences – in civic space debates that can be used in reactive and proactive campaigning. To further support a proactive agenda, we have also developed an overarching framework for a proactive narrative strategy, grounded in a longer-term strategic communications approach (See Section 5).

<-- Section 1 - Introduction | Section 3 - Attack Narratives -->

- 1Freedom House (2024) Democracies in Decline

- 2Civicus (2024) Tracking Civic Space Monitor

- 3Civicus (2023) What is Civic Space?

- 4OECD (2022) The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment With International Standards And Guidance

- 5Amnesty (2016) Russia: Four years of Putin’s ‘Foreign Agents’ law to shackle and silence NGOs

- 6See the Civicus Monitor to see the different levels of shrinking of civic space around the globe.

- 7Civicus (2019) Against the wave: Civil society responses to anti-rights groups; Fundamental Rights Agency (2021) Protecting civic space in the EU; Fundamental Rights Agency (2023) Protecting civil society – Update 2023; International Centre for Not-for-Profit Law (2018) Effective Donor Responses to the Challenge of Closing Civic Space; OECD (2022) The Protection and Promotion of Civic Space: Strengthening Alignment With International Standards And Guidance; Open Government Partnership (2021) Actions to Protect and Enhance Civic Space

- 8Ariadne (2016) Challenging the Closing Space for Civil Society: A practical starting point for funders

- 9Freedom House (2017) Breaking Down Democracy: Goals, Strategies, and Methods of Modern Authoritarians