Section 6 – Advocacy cases countering civic space restrictions

This guide is built primarily on the analysis and lessons drawn from advocacy campaigning practice with narrative change used to varying degrees as an instrument to push back on government-led initiatives to shrink civic space in various countries. This section provides the key background information on the case studies that serve as the foundation for the advice we offer. As the Kazakh case is centred around a narrative change approach, this is the most in-depth case study we document.

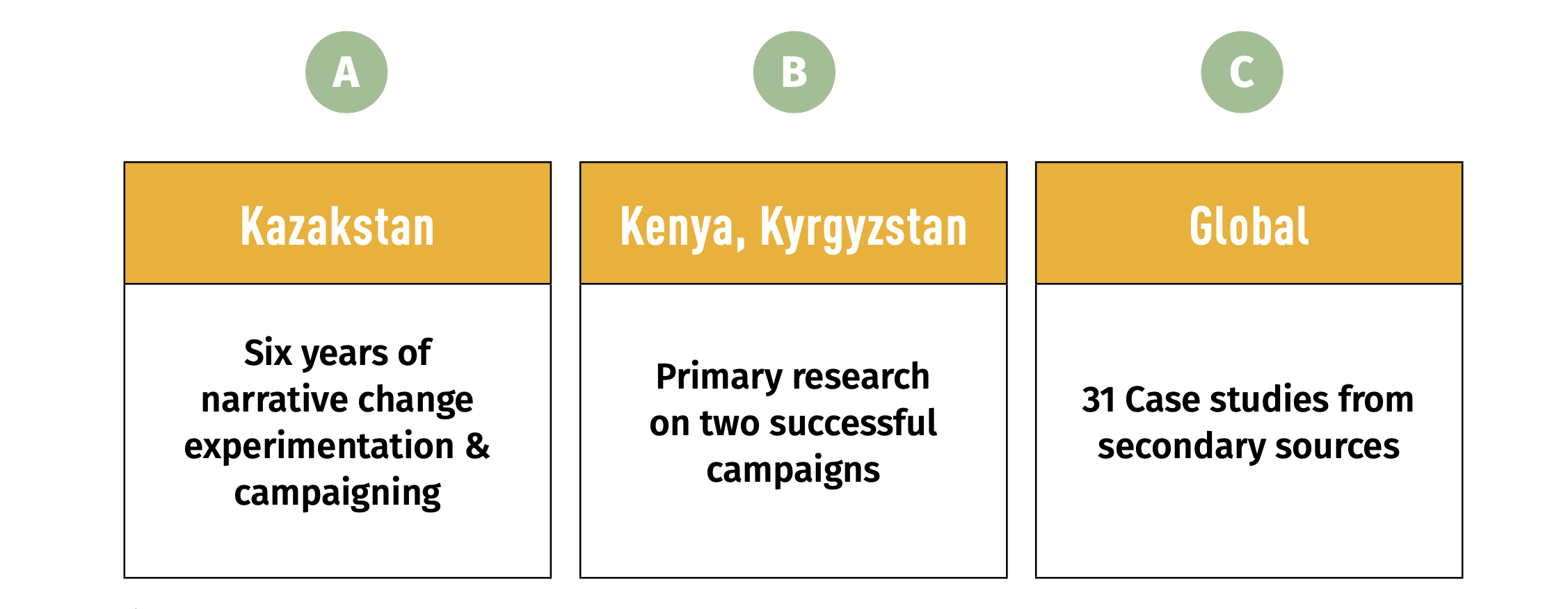

The knowledge and insights in this resource were developed in various ways: from directly supporting narrative change campaigning over a six-year period (Kazakhstan), conducting primary research and interviews with campaign leaders who led successful campaigns to overturn proposals to shrink space in their countries (Kenya and Kyrgyzstan); and analysis of shrinking civic space campaign cases written up by others. Not surprisingly, the greatest depth and insight comes from our hands-on work in Kazakhstan, followed by the primary research we conducted on Kenya and Kyrgyzstan, and finally, a more general framing comes from the cases shared in secondary sources. See the figure below for a synopsis:

Figure 12: The case practice that is the foundation of the resource

(a) Kazakhstan

(based on six years of narrative change work)

Overview

| Country | Kazakhstan |

| Civic space attack | Burdensome reporting; restrictions on access to foreign funding and partners; aggressive court challenges to suspend CSO operations; restrictions on online freedom of speech |

| Timeline | 2017 to 2022 |

| CSO response | Narrative change campaign - #Azamatbol (#Good Citizen) and coalition building to shift negative attitudes and rebuild trust in CSOs in the movable middle |

| Campaign Coalition | Led by MediaNet1 , with support of local partners PaperLab2 and Soros Foundation Kazakhstan3 (SFK); local CSO partners as protagonists; ICPA in the role of capacity builders and mentors |

| Funding Partners | Eurasia Program of the Open Society Foundations4 (OSF) and Soros Foundation Kazakhstan5 . |

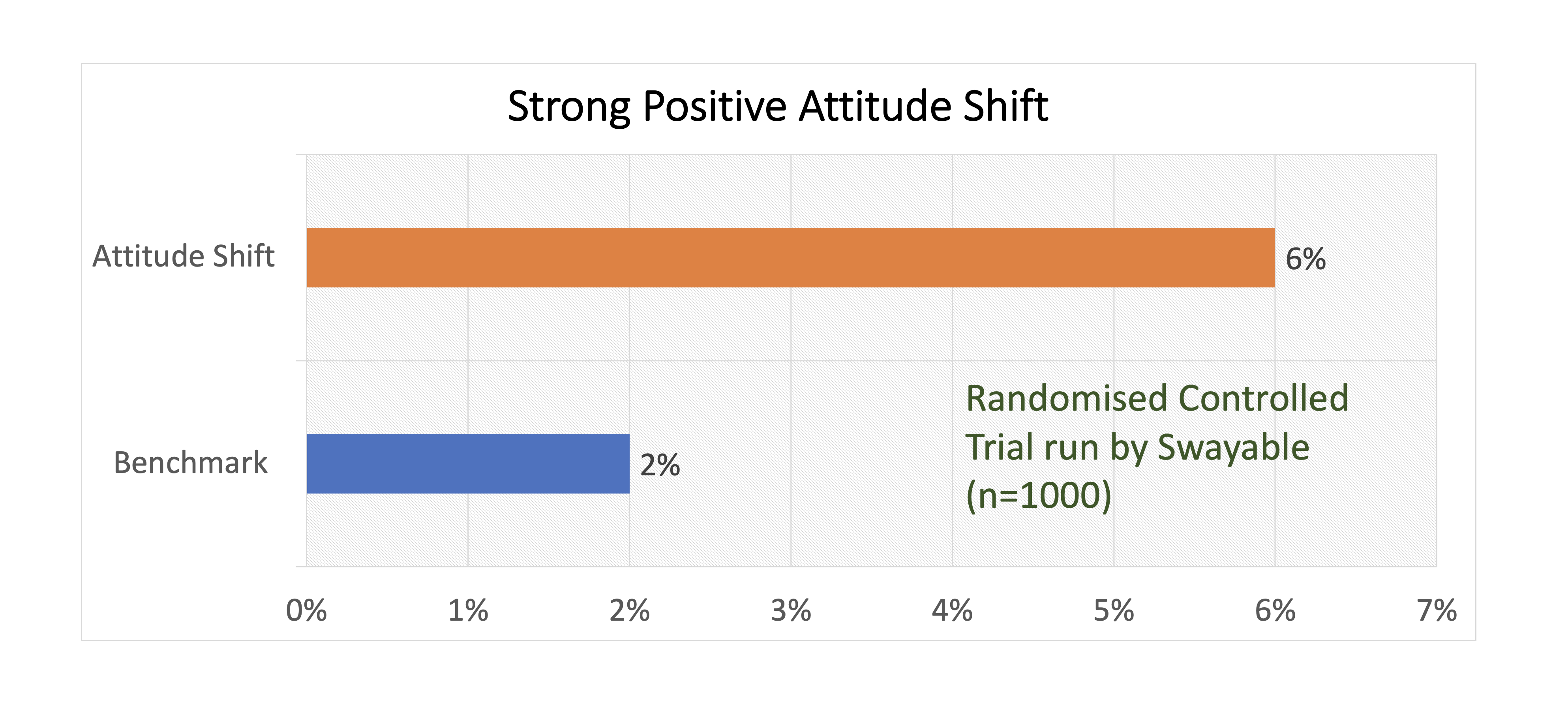

| Result | The campaign proved effective in shifting attitudes of target middle segments by +6% in the positive direction. The standard benchmark is +2% for randomised controlled trials. |

#Azamatbol (#Good Citizen)6

is a campaign designed to rebuild trust and positivity around the work of CSOs in Kazakhstan among sceptical middle groups who have been exposed to years of messaging by the government designed to undermine that trust. Azamat is a word that captures an idea of community person of good character or good citizen.

The slow squeeze on civic space has been ongoing since 2015, starting with a heavily burdensome reporting procedure that was also very aggressively policed, with organisations not fulfilling the requirements taken to court and threatened with suspension. In addition, a change in taxation laws restricted foreign funding and the possibility of working with foreign partners7

. The CSO coalition decided to experiment with rebalancing public opinion on CSOs in a more favourable direction, so it would become more challenging for the authorities to continue their steps to close civic space.

Messaging and materials

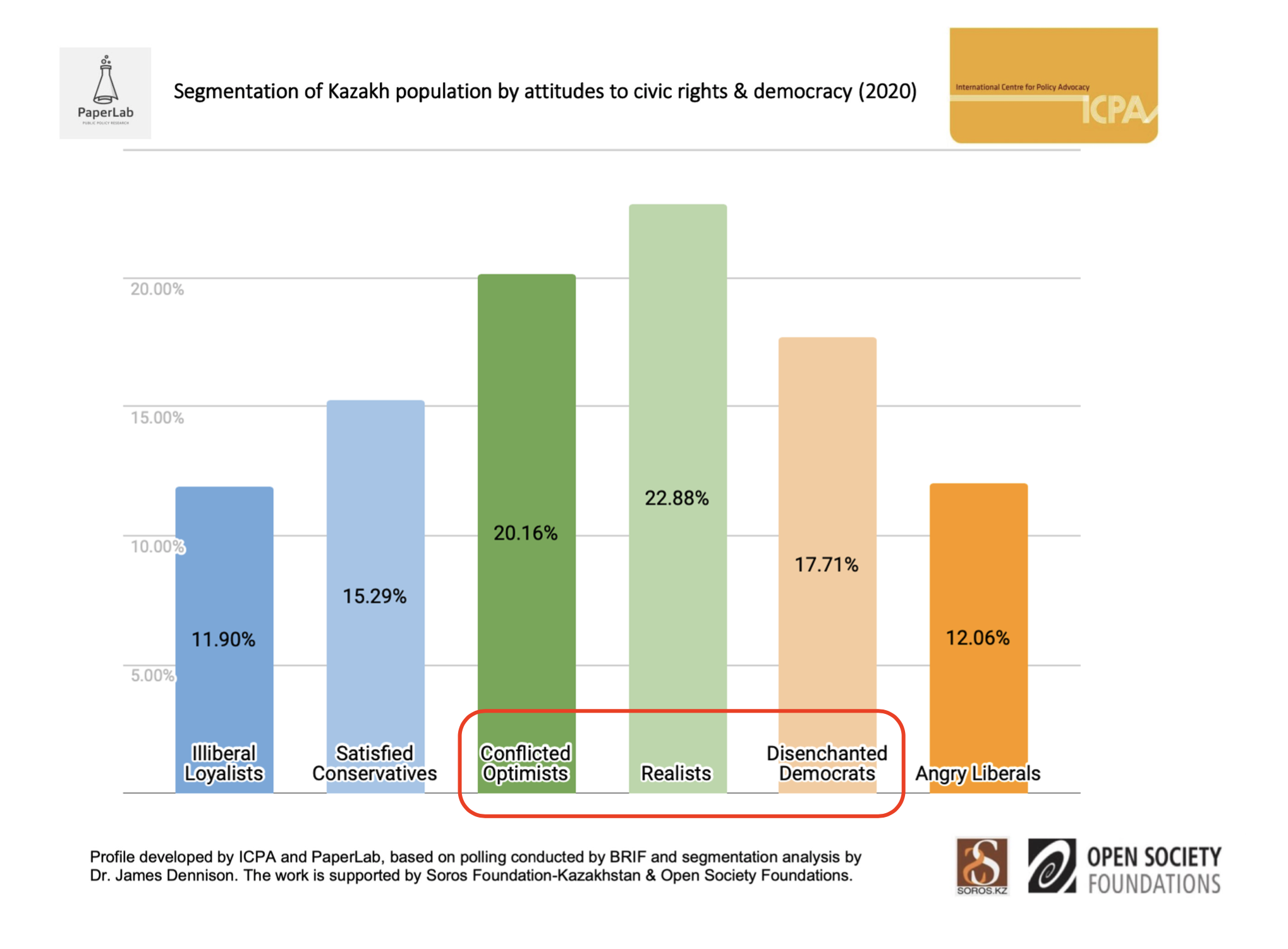

Building on new segmentation research developed in the opening stage of the project8

, MediaNet decided to target three middle segments as follows:

Figure 13: Three target middle segments for the #Azamatbol campaign

We also used a frames map of the main narrative lines in the debate on CSOs, democracy, civic rights and participation, which led to identifying possible openings to message on – especially around independent community action and charity9

. See Lesson 2 for more on the set of positive frames and also see the overview of the complete frames map in the link.

The focus of the campaign was on communicating the shared values of the civil society sector with the target segments by building stories that appealed to the following values:

Figure 14: Value appeals underpinning the #Azamatbol campaign

Example campaign materials

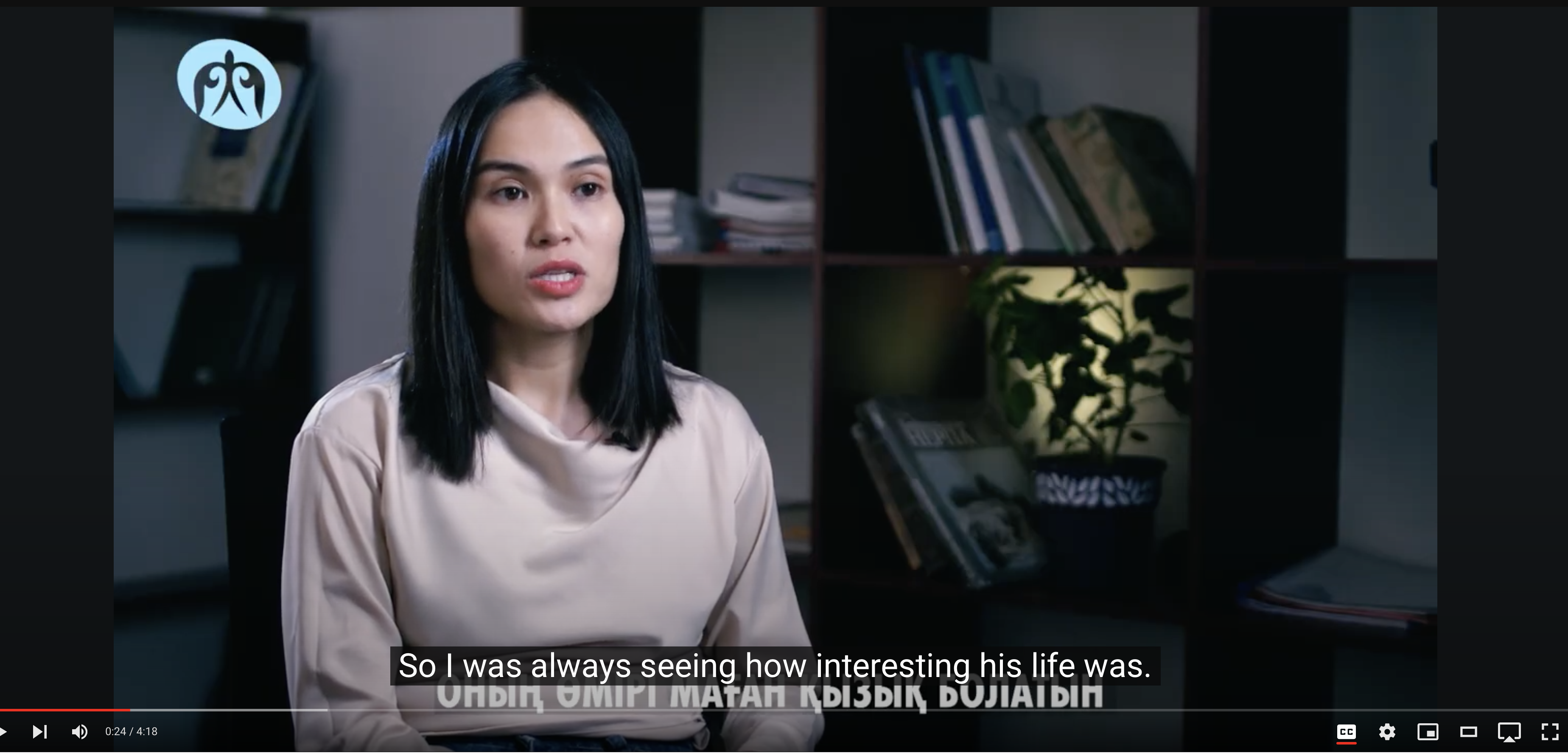

Four CSO leaders were approached to be protagonists and they shared their stories in the campaign. An example story that worked very well centred on an environmentalist called Assel, who works to protect seal populations in the Caspian Sea. At the core of the story is her strong and emotional connection to the seals she protects and her dismay at seeing their numbers fall from 2015. She also shares about the strength of her organisation and those who work with her to find a solution to protect the seals and the local Caspian Sea environment, with an appeal to shared action of local partners as the key to success. Her story is also set in a family background, as she works with her father and warmly shares many experiences with the seal population she has shared with her father from a young age. Telling what could otherwise be a dry scientific issue through a personal lens and showing that local responses are the solution brings out an authentic story that really moved opinion of the middle.

Figure 15: Example of value-driven CSO story shared (See the Assel video)

A second story that also worked well was from a CSO leader called Aizada, who supports children with disabilities (See the Aizada video).

The following are two examples of memetic material produced for the campaign and shared on social media:

Figure 16: Example of campaign visuals over two rounds of the campaign

First picture: The idea of the yurt appeals to a very warm traditional idea of community and independent community action in Kazakhstan. The choice of the ant (which has a positive connotation) reinforces the idea of an active community with outsized strength. The copy is a well-known local phrase in Kazakh that means lots of hands reach heaven, similar to the phrase ‘many hands make light work’, but even more hopeful!

Second picture: Portraits with key quotes for the four protagonists were also used. This is the one for Assel and the quote says the following: “Who else but us will protect Caspian seals? The support of concerned people, partner organisations and the state gives the team of the Institute of Hydrobiology and Ecology confidence that together we will save the Caspian Seal”.

Testing, evaluation and results

The campaign was launched on social media and run mostly on Facebook and Instagram to reach the target segments. In addition, the campaign worked with online influencers to further share the content and access middle groups, e.g. an Instagram influencer around motherhood. In addition, media outlets covered the campaign in more mainstream press.

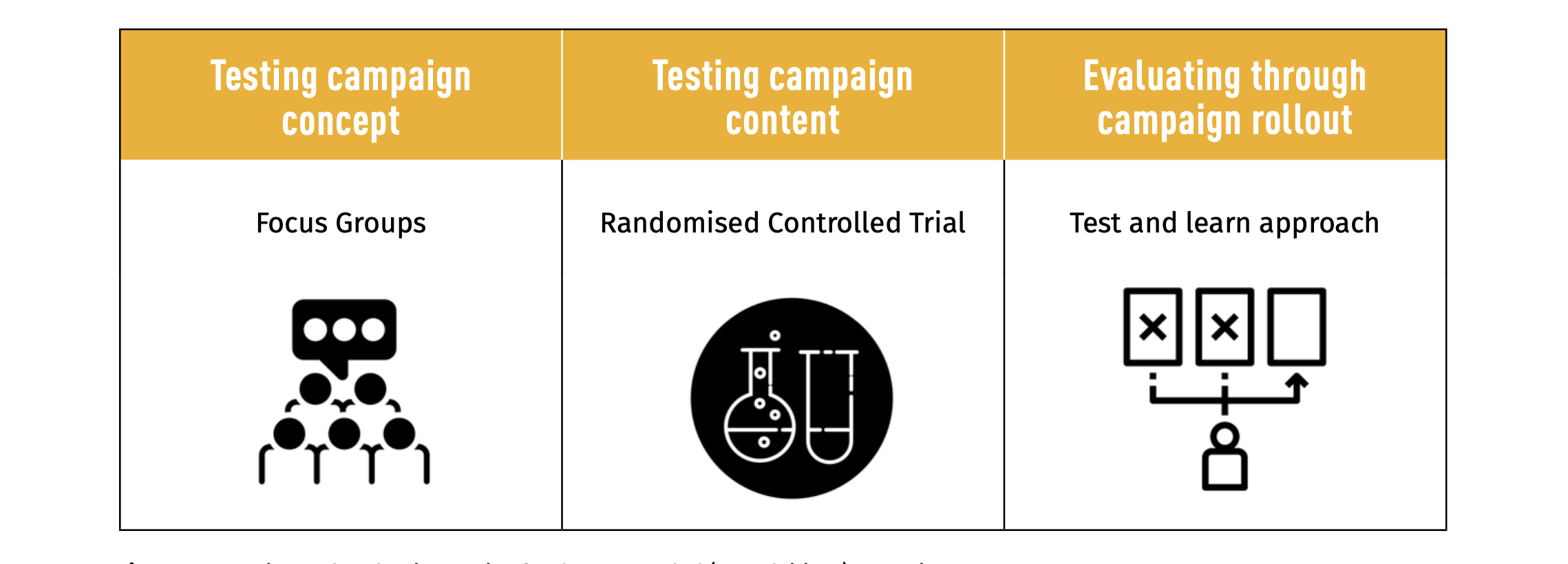

Then, through the various stages of development we navigated the following testing and validation process:

Figure 17: Testing and Evaluation Design for the #Azamatbol (#Good Citizen) campaign

See the case box in Lesson 10 for more on the strategy and our message testing resource for an introduction to each of the methods.

After two rounds of campaigning, there was significant reach to middle groups and high levels of engagement with the material. The most significant result was measured by running a randomised controlled trial on a group of 1,000 people where a test group saw a campaign video and answered survey questions on CSOs, and a control group who saw a general public information video and answered the same set of questions10

. Having segmented the results, it showed that the campaign material produced a +6% positive attitude shift among middle groups (standard benchmark is +2% for such tests). These results show the potential to go to scale with positively focused CSO stories based on shared values that demonstrate the contribution and value of the sector to the public.

Figure 18: The materials produced a 6% positive attitude shift on CSOs in the movable middle

- 1MediaNet Website

- 2PaperLab Website

- 3Soros Foundation Kazakhstan Website

- 4Open Society Foundations, Eurasia programme

- 5Soros Foundation Kazakhstan Website

- 6MediaNet (2021) Azamatbol Campaign Facebook Page

- 7ICNL (2024) Civic Freedom Monitor: Kazakhstan

- 8See an overview of all six segments from this research.

- 9This frames map was developed based on an internet scraping approach commissioned from Bakamo Social.

- 10The test was commissioned from Swayable.

(b1) Kenya (based on primary research)

When we began work in this field in 2017, we asked experts for advice on where CSO coalitions had been successful in pushing back on government attempts to shrink civic space. As many mentioned Kenya and Kyrgyzstan, we chose to research these as case studies to learn from. It is worth noting that the pressure on civil society in both these countries has continued since these hard-won victories.

Overview

| Country | Kenya |

| Civic space attack | Restriction on foreign funding, burdensome reporting, active deregistering of CSOs for non-compliance, increased surveillance powers and public vilification of CSOs |

| Timeline | 2013 to 201711 |

| CSO response | Multi-pronged public, international, litigation and parliamentary campaign to defeat the initial proposal, and building of a CSO platform |

| Result | The proposal was first defeated in parliament in 2013 and continual monitoring and push back of new initiatives to reintroduce similar amendments continued to 2017. |

Over the five-year period in focus for this case study (2013-2017), the Kenyan government of the time made multiple attempts to shrink civic space from restricting the use of foreign funding to burdensome reporting laws, to actively deregistering CSOs for non-compliance to a public campaign vilifying CSO leaders as ‘enemies of the state’. This was done during a period of legislative chaos when amendments to a law on public benefits organisations was debated back and forth, and at the same time a very aggressive executive body (NGO Coordination Board) went ahead with these actions to shrink space.

A broad 50-member CSO coalition, led by the Civil Society Reference Group12

, used a wide variety of tools over that time to push back on these initiatives including public/social media campaigns, street protests, strategic litigation, and building opposition support in the parliament and among international organisations. The arguments made centred primarily around the positive contribution of the sector and its leaders to development, social services and the economy, as well as the immediate loss of essential services (such as health care), development funding and standing in the international community if the laws were passed13

.

Figure 19: Example of online meetings with CSO leaders who were attacked as ‘Enemies of the State’14

.

As shown in Figure 19, an example of the reframing done in the campaign was to hold online meetings with CSO leaders who had been vilified by the government as ‘enemies of the state’. In these meetings, the CSO leaders took questions and talked about their own lives, their families and communities and what motivated them to become part of the civil society sector and why the sector is important to their community.

To develop this case, we conducted an analysis of key documents and interviewed the Executive Secretary of the Constitution and Reforms Education Consortium (CRECO)15

in Kenya, who was a key player in the Civil Society Reference Group (CSRG) coalition.

Although this push back was successful, it is worth noting that pressure on civic space and rights continues to the present day16

.

- 11The work of the coalition is ongoing.

- 12Civil Society Reference Group Facebook Page

- 13Heinrich Boll Stiftung (2016) Under Pressure: Shrinking Space for Civil Society in Africa; Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (2019) Preventing Civic Space Restrictions: An Exploratory Study Of Successful Resistance Against NGO Laws.

- 14Enemy of the State KE blog (2013) 15Constitution and Reforms Education Consortium (CRECO) Homepage

- 16Civicus (2022) Country Brief Kenya: Overview of recent restrictions to civic freedoms ahead of 2022 elections.

(b2) Kyrgyzstan (based on primary research)

When we began work in this field in 2017, we asked experts for advice on where CSO coalitions had been successful in pushing back on government attempts to shrink civic space. As many mentioned Kenya and Kyrgyzstan, we chose to research these as case studies to learn from. It is worth noting that the pressure on civil society in both these countries has continued since these hard-won victories.

Overview

| Country | Kyrgyzstan |

| Civic space attack | A Foreign Agent’s law similar to the Russian model |

| Timeline | 2013 to 2016 |

| CSO response | Public, international and parliamentary campaign to defeat the proposal |

| Result | The proposal was defeated in Parliament in 2017 |

In 2013, the Kyrgyz government tabled a Russian-inspired ‘Foreign Agents’ law and this began a three-year campaign by a CSO coalition until the proposed law was finally defeated in 201617

. The campaign combined public campaigning, mobilisation and pressure from international organisations (e.g. OHCHR/UN, OSCE, EU), as well as working closely with parliamentary opposition to defeat the proposal.

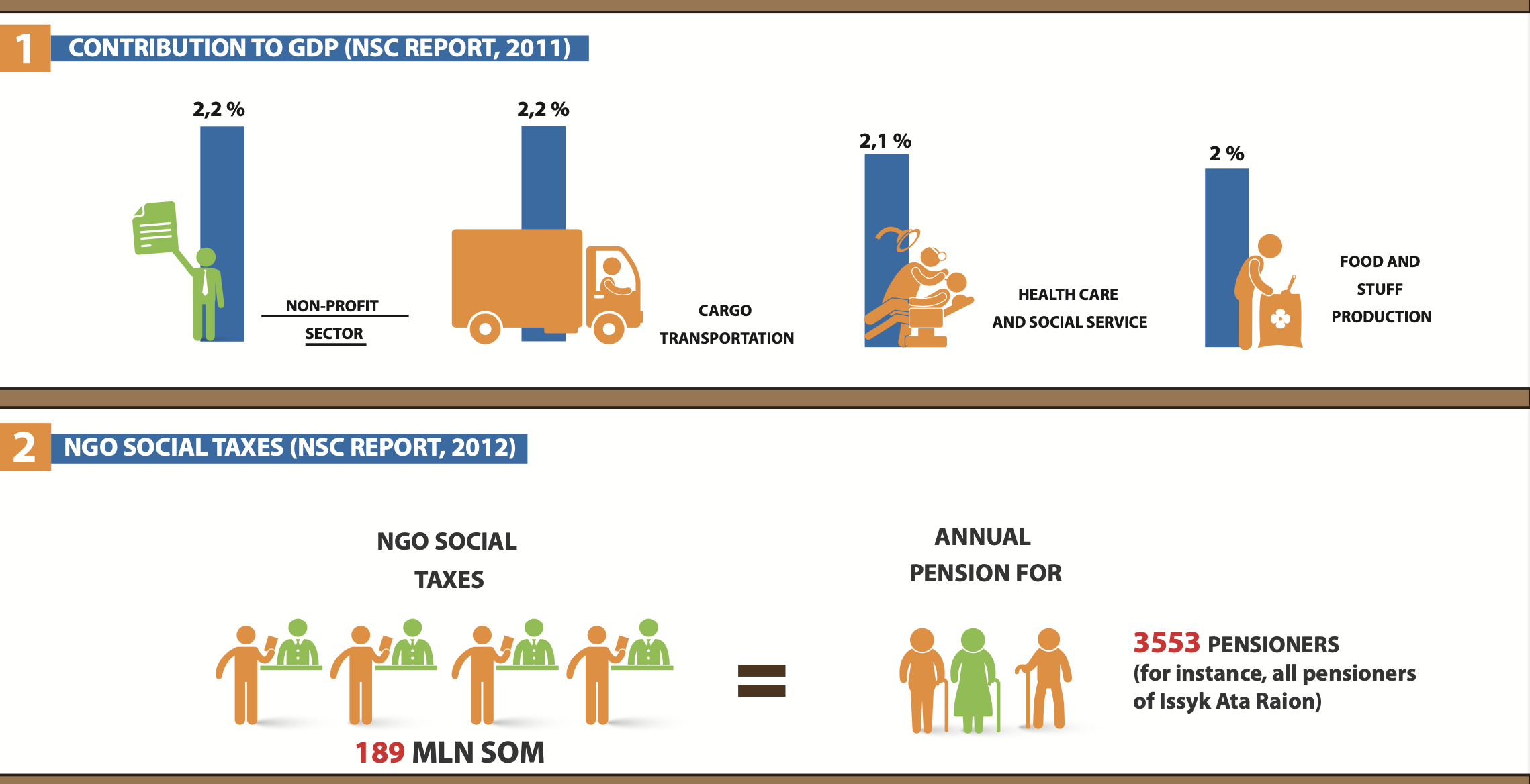

Kyrgyz campaigners reframed the debate away from foreign agents to the significant financial contribution of the sector to the overall economy and also its vital role in service provision of health care (See Figure 20 showing how this data was presented). They also built an argument around the risks of the country losing its reputation as an “island of democracy” in the Central Asian region, should civil society be restricted18

.

Figure 20: An example of the striking facts used in the campaign to talk about the contribution of the sector

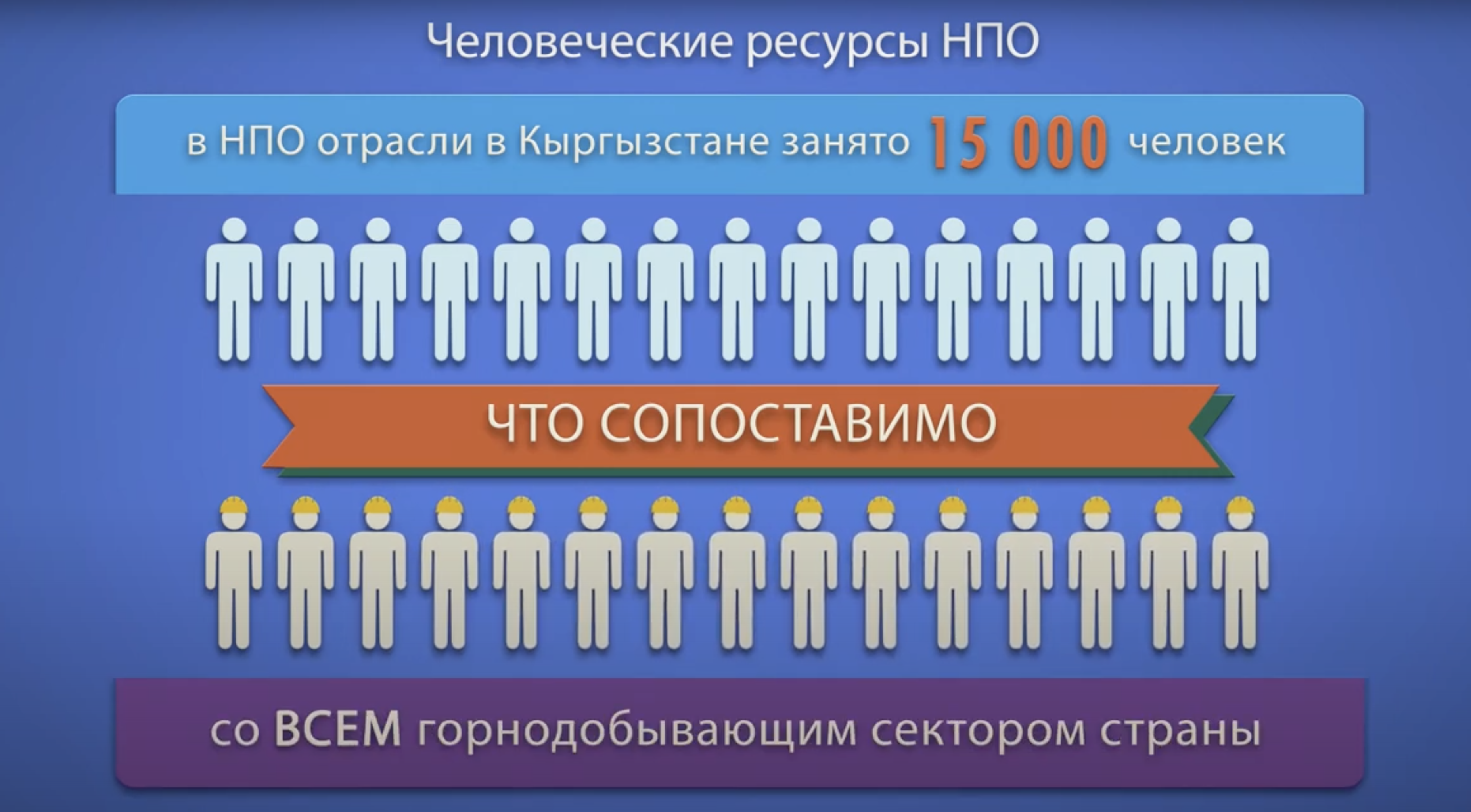

To pull the whole argument together for parliamentarians, campaigners put together a video showing how embedded CSOs are in supporting citizens and the state19

. The video also shows the extensive broad-based coalition who supported them or the “choir of arguments” as they called it, including CSO leaders, civil servants and MPs.

Figure 21 – Example argument made in the video: The CSO sector employs 15,000 people, which is the same as the whole mining sector in Kyrgyzstan.

To gain insights into the campaign, we completed an analysis of documents and interviewed the director of the Civic Participation Fund, who was a leader in this coalition.

It is worth noting that as we finalise this work, that the situation in Kyrgystan has changed for the worse and a foreign agents law very similar to the one discussed in the case study was passed in April 202420 .

- 17Civicus (2016) Resilience of Kyrgyzstan CSOs pays off as parliament throws out ‘foreign agents’ Bill; Guardian (2016) Disputed 'foreign agent' law shot down by Kyrgyzstan's parliament.

- 18Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (2019) Preventing Civic Space Restrictions: An Exploratory Study Of Successful Resistance Against NGO Laws.

- 19See campaign video showing their range of supporters (In Russian - Turn on & adjust Closed Captions to see it translated into your language of choice)

- 20The Diplomat (2024) Kyrgyzstan Adopts Law Targeting Foreign-Funded NGOs

(c) Secondary sources on cases

To widen the evidence base for this resource, we drew on 30 case studies of various initiatives across the globe designed to preserve civic space which were compiled from two main sources:

- 16 long case studies from World Movement for Democracy (2021) Civic Space Case Studies21 ;

- 14 short case studies from LifeLine (2020) Advocacy in restricted spaces: a toolkit for civil society organisations22 .

These cases covered work done in Europe, Asia, Africa, Russia and the Caucasus, Middle East, Central and South America. We conducted the case study analysis mainly to confirm the similarity of patterns of attacks and responses around the globe, with two cases, from Hungary and Egypt, also used in the lessons section as illustration.

- 21World Movement for Democracy (2021) Civic Space Case Studies

- 22Lifeline (2022) Reanimating civil society: A Lifeline guide for Narrative Change