Chapter 5-2 The stories & protagonists

5.2 Strategic foundations for the story development process

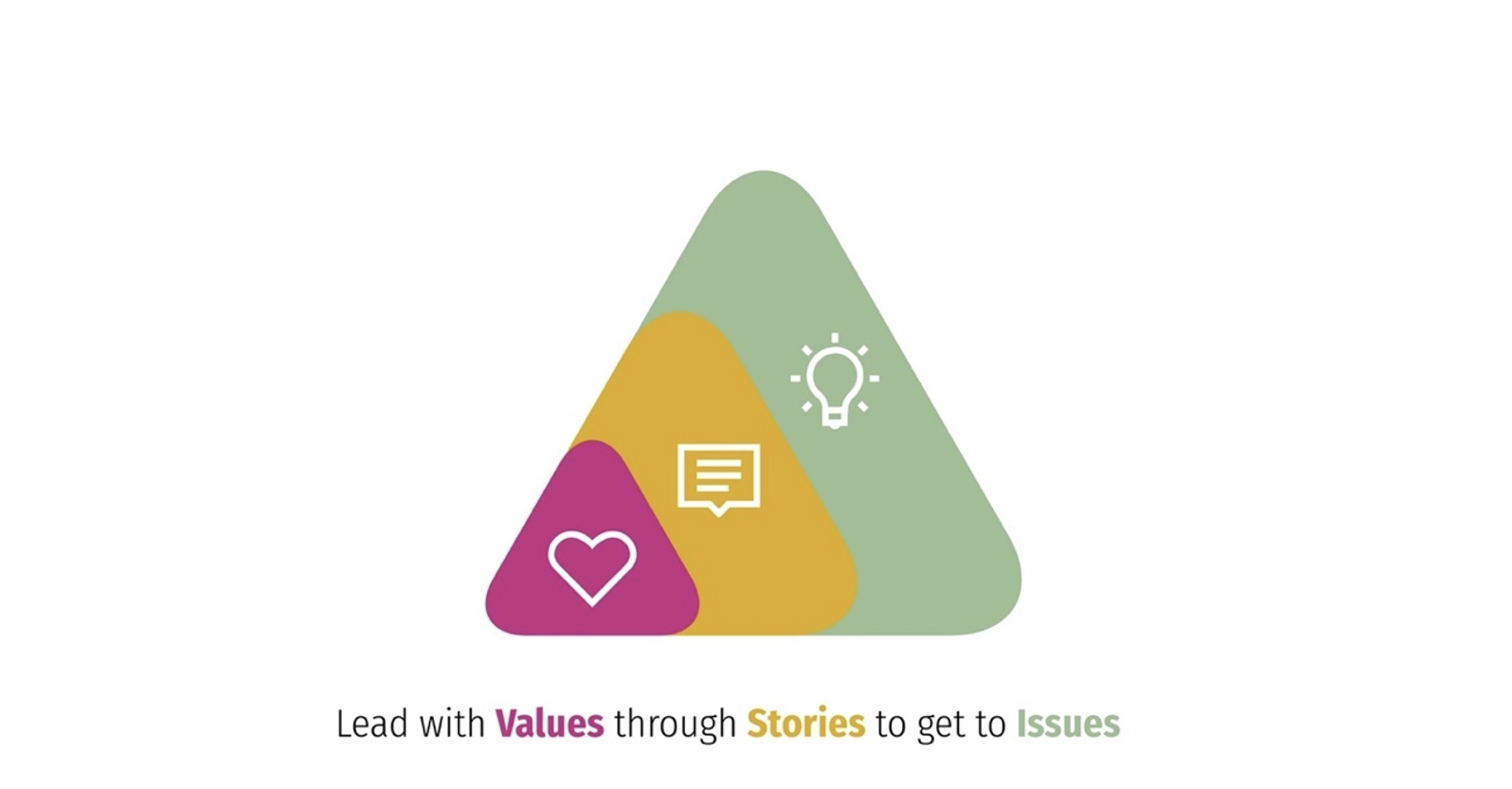

Stories are the connective tissue or bridge between your value appeal and the issue you want to discuss and this is why they are at the heart of the #KommMit pilot. The following figure synopsises this relationship:

Figure 18: The values-led intervention logic in ICPA’s narrative change approach

Values are the foundation of narrative change, but without illustration, they can remain quite vague and conceptual. The need to unpack values through stories is really clear during focus group discussions we run as part of every narrative development process. Strong, authentic storytelling plays a key role in making a value appeal accessible, striking and lays a foundation for the issue you want to discuss. Good storytelling humanises the issues you’re addressing, which in essence, brings your values to life.

To recap the key strategic foundations of the #KommMit pilot (as detailed in Chapter 4) that informed the story telling process:

- The chosen value appeals (interdependence/solidarity, participation, stability and intergenerational future) worked and brought positive and constructive reaction from ‘The Established’. This was proven in the focus groups and the survey on topline narratives, indicating good potential that the target audience could be moved on this issue.

- Around the issues in focus, there were two specific challenges identified: following focus group testing, the working group really wanted to tackle two recurring assumptions about Muslims in Germany in order to move the narrative into a post-migrant space that reflects the reality of German society in the 21st century:

- the assumption by the target group that being Muslim automatically means you’re a foreigner, which we synopsised as “Muslim = foreigner”;

- that success stories of integrated Muslims are the exception rather than commonplace in Germany.

Considering the long-term goals for the project, storytelling is also an element and driver of the solution. The current problem and future solution would seem to lie in the strategic communications target of presence. Put simply, building the presence of a narrative means it becomes a regular part of the public discourse in the debate on Muslims, which currently is filled with stories of parallel societies and potential security threats. Therefore, a key element of the strategic communications solution lies in tipping the balance away from these normalised far-right frames in the discourse to share stories of the normal everyday lives of Muslims that the pilot has shown already can shift the dial in a positive direction on this issue among middle groups. Put simply, broadly sharing the stories of simple normal lives is the reframe!

5.3 Working with protagonists

Telling and sharing stories of the everyday lives of Muslims in Germany is at the heart of the #KommMit pilot. Hence, finding protagonists who were open to telling their story and also happy to share their stories with the public was crucial to achieving this goal. This proved to be more challenging than the team anticipated: while a number of people approached were interested and supported the ambitions of #KommMit, they were worried about the potential backlash online or in their communities if their stories were made public. Additionally, a few others who were also interested just couldn’t commit the time needed to be part of the project.

In the end, the #KommMit pilot tested stories and social media content for three tradespeople protagonists: Ayoub, Yusuf and ‘Murat’. The protagonists agreed to be part of the project at different levels:

- Ayoub was happy for us to interview him, make videos and share his story on social media.

- Yusuf consented to have his story shared on the project website. As he didn’t have time for the interview process, his story was built on his existing social media profile and website for his business.

- ‘Murat’ was initially fully on board, but after the interview was conducted, he decided that he didn’t want his story shared publicly, fearing any kind of backlash in the small community where he lives. However, he did give permission to test his stories under the fictional protagonist name ‘Murat’1 .

Advocates need to take a lot of care when working directly with protagonists, and there is much well-founded criticism around the recruitment and treatment of protagonists in public campaigns where the voice of the affected group (e.g. migrants) is paramount. Much of this centres on how much agency protagonists have and how they are portrayed in public campaigns. Building on our extensive experience in this field, we sharpened our processes and sensitivity levels through working together with the activist group developing the #KommMit project. The main insights and learnings from this part of the work are detailed in the following two sections.

5.3.1 Safety & consent are paramount in working with protagonists.

In supporting narrative change work centred around authentic storytelling with protagonists, we are guided by the principles outlined by James Spradley in his seminal work, i.e. that we “must do everything to protect the physical, social and psychological welfare and to honour their dignity and privacy2 .” As protagonist safety is the top priority, we have designed and are committed to an open communication and consent process at key stages in the story development process that allows protagonists to adapt, reject and/or withdraw their story and participation completely. In practical terms, this means the following:

Communicating aims is an unfolding process, rather than a once off.

This principle was particularly important and as we spent two days with protagonists in the interview process, and devoted time before, during and after the interview discussing what being a protagonist in the #KommMit pilot project entailed: this gave time and space for them to understand the aims and approach and clarify these in more depth over the time spent together during the interview. As noted above, even after the interview process, one protagonist – Murat – withdrew from the #KommMit pilot, which was his right. Protagonists appreciated these multiple opportunities for clarifying and better understanding the #KommMit pilot and their role in it.

Right to remain anonymous, but also warned of risks (even unintentional)

We offered protagonists the choice to remain anonymous at many levels: by not using any name, replacing their real name, and/or by not revealing their location. We openly discussed with protagonists that there could still be a risk even if they chose the anonymous route, as their face could be recognised by someone in their local community. While only one protagonist chose anonymity, they all expressed their appreciation of this option and the care we showed them.

Allow protagonists to say things are off the record.

Following journalistic principles, protagonists could say at any time that what they were sharing during the interview was not to be used in the actual project material in their story. The two protagonists interviewed did share some more personal things which they requested to be off the record. We fully complied with this request, and considered this deeper sharing to be an expression of trust and confidence that was built through the recruitment and interview process.

Make stories available for approval before going public.

Finally, in keeping with the principle that consent is a process rather than a once off, protagonists were asked to signed off on all the content and material featuring them before it was shared in public as part of the #KommMit project. The bottom line we communicated from the beginning with protagonists was that they have the final say and nothing gets shared publicly without their consent and formal green light.

5.3.2 Lessons from the protagonist recruitment process

As noted in the opening of the chapter, recruiting protagonists for the #KommMit project proved challenging, given that the target middle audience for this narrative change project went beyond the supporter base which most were more familiar with for public campaigns. We shared openly that ‘The Established’ target audience were sceptical about Muslims. For advocates interested in working with protagonists for middle-oriented narrative change work, we offer the following lessons from the #KommMit experience.

Be prepared to invest time in recruitment.

Recruiting the three protagonists who signed up to be part of the pilot at different levels required a significant investment in time and effort. Virtually all members of the team contacted and spoke at least one other person who in the end didn’t come on board for fear of potential backlash and/or availability reasons. More specifically, to successfully recruit three protagonists, a total of 10 people were approached. Time was invested with each in communicating the goals and focus of the #KommMit pilot, the role of protagonists, and in relationship and trust building.

This low uptake happened even though time was spent reassuring potential protagonists that such value-driven projects get mostly warm responses on social media, with no large-scale attacks or hate speech. Even when we explained that the pilot was limited to social media and there would not be any media coverage, nor were they expected to represent the project live in any way, this didn’t alleviate most people’s fears. It should help the recruitment process to now be able to share the materials and results from the actual #KommMit pilot rather than talk about it in the abstract. It’s especially important to show that the #KommMit content didn’t lead to any significant hate speech or backlash – hopefully, this should reduce the fears of potential future protagonists.

The protagonists who chose to come on board already had some public presence.

Ayoub works in a large bakery that had already received awards for their commitment to diversity and he and his colleagues had been interviewed in the media as part of reporting on these awards. In addition, Yusuf already has a significant social media profile on Instagram and YouTube, in which he promotes his butchery business and also takes on discussions on the differences and similarities between bio and halal meat. Therefore, they both had some experience of the kind of public response that can come on these topics, and this proved to be one reason for their willingness to be part of the pilot.

Be prepared for drop outs and have a plan B.

When there’s a serious commitment to safety and a high bar for consent, advocates should prepare for some protagonists to drop out or not make themselves as available as you wish. So, ultimately you need to prepare back up plans. For example, Yusuf could not commit to the interview process, but did consent to our request to instead build a story based on his existing social media profile. This is the second-best option, and served as a useful addition to the project.

Be pragmatic and start the work with the ones who come on board.

The three protagonists who ended up being part of the pilot were all male tradespeople – baker, butchery businessman, and carpenter. The team had also tried to recruit from other trades where a higher proportion of women could be expected, e.g. hairdressers, tailors, but unfortunately, to no avail. So, it is a limitation of the pilot that no female protagonist features, and this gap becomes a priority for future recruitment of protagonists.

One protagonist came to Germany as a refugee six years ago, one was born and brought up in Germany and is the child of immigrants, and the third is the child of German parents who converted to Islam. The working group didn’t want to focus on refugee stories, as the focus of the pilot was on post-migrant German society, but this protagonist’s story still worked out well.

Given the challenges of recruitment, you are often put in a place when those willing and able to get involved are not an ideal representation of what you want to put across, but there are pragmatic realities and limitations that often need to be faced in such work, especially in getting a project such as #KommMit off the ground at the pilot stage.

Reflect on the insights and lessons we shared above about working with protagonists, and consider the following questions related to your work:

- What is your experience recruiting and working with protagonists for public advocacy campaigns?

- How was the experience? Which of the challenges we shared are familiar for you and which are new?

- Can you think of potential protagonists from your network who could fit the #KommMit project?

- Would you be interested in developing stories with protagonists following the value-based storytelling approach at the heart of the #KommMit project?3

<-- Chapter 5-1 | Chapter 5-3 -->

- 1 To protect his identity further in the testing process, we didn’t reveal his location or use any pictures of him or his workplace.

- 2Spradley (1979) The Ethnographic Interview Holt Rinehart & Winston, New York.

- 3One of the ways to adopt the strategy would be to add to the exising bank of stories on https://komm-mit.org as proposed in Chapter 7.